No products in the cart.

The Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Nigeria-Biafra War, broke out on July 6, 1967, and ended on January 15, 1970. An estimated three million people on both the Nigerian and Biafran sides lost their lives during the war.

It’s been 55 years since the civil war broke out and its impact can still be felt, especially among those who lost their loved ones during the 30-month conflict.

1966 Military Coups

On January 15, 1966, a group of junior officers in the Nigerian Army incited a bloody coup to end Nigeria’s First Republic. These officers, due to their inexperience, would ultimately fail to take power directly. However, they were successful in truncating the government and eliminating some top senior officers in the military.

Contents

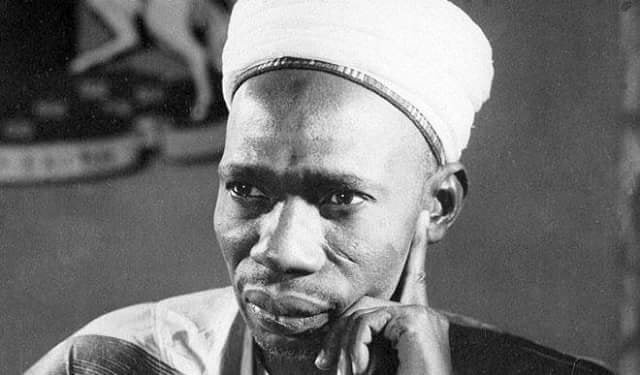

Initially, Major Kaduna Nzeogwu and his fellow plotters were viewed as national heroes. The killings during the coup, however, gave a different appearance. Sir Ahmadu Bello, Premier of the Northern Region, the Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Chief Samuel Akintola, Premier of the Western Region, the Minister of Finance, Chief Festus Samuel Okotie-Eboh and some other senior military officers of the Nigerian Army were killed in cold blood.

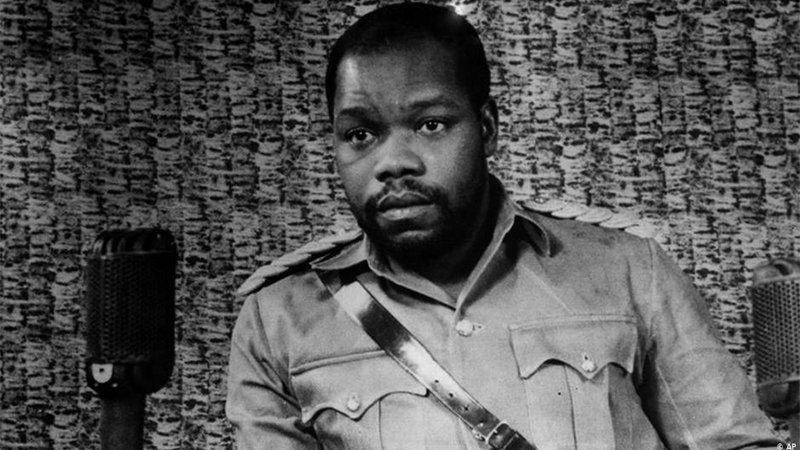

Major-General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, the most senior military officer in the Army to survive the coup, became Nigeria’s first military Head of State. Ironsi had escaped the plotters and was able to resist the coup. An Igbo soldier from Umuahia, present-day Abia State, Aguiyi-Ironsi pressurized the rump cabinet of the Balewa administration to hand over all political powers to the Nigerian army.

This action did little to allay the fears of the northerners who feared the domination of the Igbos. The Head of State, on May 24, 1966, then went further to promulgate Decree 34 which was to nullify the federal structure and approve a unitary system. The North viewed the decree as an attempt by the Igbos to dominate and take control of everything.

As a result, there was a widespread anti-Igbo riot in May and June of 1966 where the Igbos and some other southerners were killed in the major cities of Kano, Kaduna and Bauchi. Then on July 29, 1966, northern soldiers turned on their fellow Igbo officers and killed them in a bloody countercoup. This countercoup has been described as the bloodiest in African history.

Many high-ranking Igbo soldiers including General Aguiyi-Ironsi lost their lives and the northern dominance was restored with the elevation of Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon as Head of State. In the East, where Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu controlled, the countercoup was unsuccessful and not a single soldier lost his life.

The Gowon-Ojukwu Rivalry

As Head of State, Yakubu Gowon abrogated Decree 34 and restored the federal system. But his authority was questioned by Ojukwu who said Gowon had no right to become a Head of State as there were senior military officers that would have succeeded Aguiyi-Ironsi. However, these senior military officers were southerners. Gowon, to his advantage, was the most senior northern officer to have survived the January coup.

This strained relationship between Ojukwu and Gowon would be aggravated with the ethnic cleansing of the Igbos in the north. Although Gowon and his military governors condemned the killings, the situation did not abate.

An ad hoc constitutional conference held in September 1966 to decide on the future of the country also failed. While some delegates requested that a confederal system replace the federal system, the eastern delegates demanded that regions that desire to secede from the federation be allowed. The conference ended abruptly with increased killings of the Igbos in the north.

Recall that, on August 1, 1966, Yakubu Gowon had declared on air as Nigeria’s new military head of government. Interestingly, Emeka Ojukwu also went on air to counter Gowon that he would not accept the authority of the new Head of State, expressing his desire to protect his people who had suffered indiscriminate killings in the north.

In view of this, a peace meeting was held in Aburi, Ghana, in January 1967, where Gowon had agreed to all of Ojukwu’s demands but later reneged on his own side of the deal by promulgating Decree 8. Ojukwu was angry and threatened that unless all the demands agreed at Aburi were met, the East would have no option but to secede from the Nigerian federation.

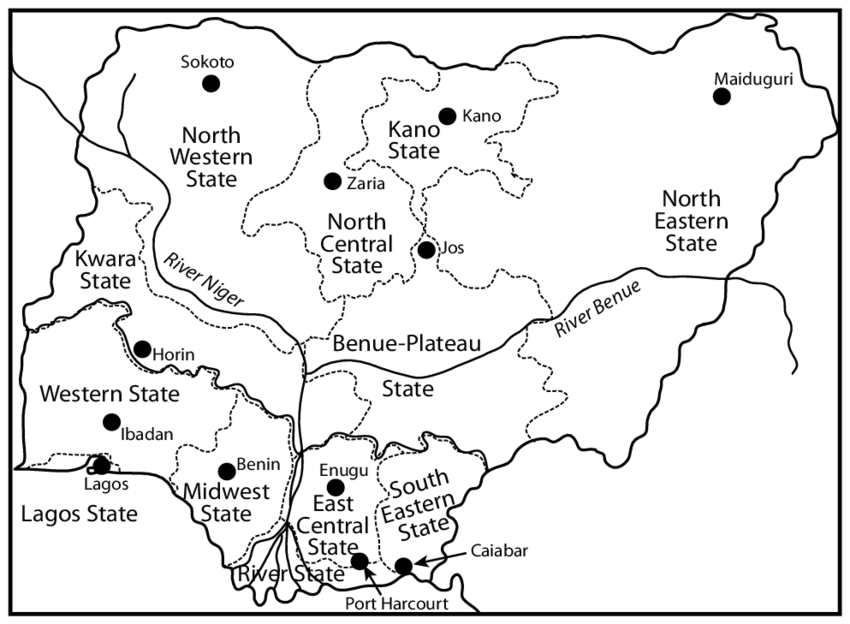

In expectation of the eastern secession, Gowon, on May 27, 1967, weakened the support of Ojukwu’s region by the creation of 12 new states to replace the four regions of Nigeria’s First Republic. Six of the states had since the 1950s demanded their creation. They were mostly minority groups. These minority groups also joined the federal troops to fight in the civil war which was to bring the eastern region back to the federation.

With Gowon’s announcement of the creation of more states, the stage was set for the eastern region to secede and Ojukwu declared the Republic of Biafra on May 30, 1967.

The Nigerian Civil War

The Biafran Republic had declared its independence and wanted to break free from the Federal Military Government of Nigeria. However, Gowon could not allow the secession to take place for the following reasons:

First, there was the belief in the practicability of Nigerian unity by the Federal Government and they wanted to put in the work to achieve this unity. Also, the secession of Biafra would trigger the secession of other minority groups within the federation.

In addition, the lands of Biafra occupied 67% of the known petroleum reserves in Nigeria. It would therefore be suicidal to the Nigerian economy if Biafra was allowed to secede.

The Federal Government and Gowon personally asserted that the fight was not directed against the Igbo as a population group, but against those available for secession.

International bodies initially refused to be a part of the war. The OAU treated the civil war as an internal Nigerian conflict. The United States chose to sit on the fence and this infuriated the Federal Government which later turned to the Soviet Union for support.

A few countries in Africa, however, supported the movement of the Biafran Republic during the Nigerian civil war. The first African President to recognise Biafra was President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. His recognition of the Republic, according to Chinua Achebe, “meant nothing in military or material terms, but it assured us – the effect it had on us was electric.”

Gowon would put in measures to stifle the resilient nature of the Biafran troops and in general, the Biafran Republic. His strategy focused on the isolation and impoverishment of Biafra.

His creation of new states was done to isolate Ojukwu and make political matters more difficult for the Biafran government.

The Head of State also placed a blockade on the coast and ensured that a military cordon surrounded the country. This made it practically impossible for Biafra to ship food and other items into or out of the country. Also, there was a change in currency. This meant that the Nigerian currency garnered by the Biafran Republic before the civil war became useless.

The Biafran Republic recorded military success in the first few months of the civil war. They were able to ward off the federal troops and kept their region secured. However, this was not to last.

The impact of Gowon’s economic strategy began to take its toll on the people. The blockade which surrounded the Biafrans led to a humanitarian disaster. Hunger prevailed in the land and starvation escalated amongst the people. This led the Biafran Republic to make claims that the Federal Government was using hunger and genocide to win the civil war.

The claim of genocide led many volunteer bodies to break relief flights into Biafra, carrying food and relief supplies. The Catholic Church worked together with the International Red Cross Society to provide humanitarian aid to the people of Biafra.

The Biafran troops were able to hold out the Federal troops for a few months until late 1969 and early 1970. However, on December 23, 1969, the Nigerian federal forces launched an attack against the Biafrans whose army collapsed and was overrun by the federal troops in January 1970.

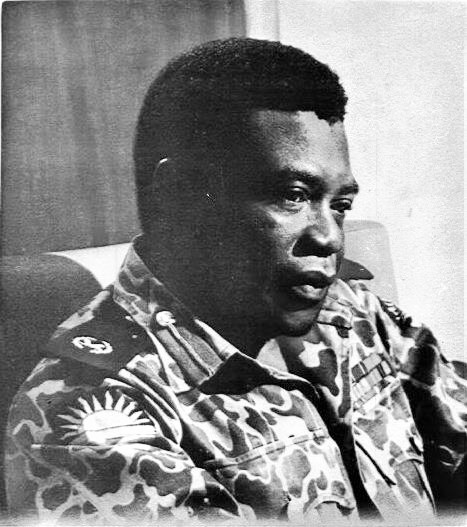

With defeat staring at his face and to save himself from public humiliation and death, Ojukwu fled to Cote d’Ivoire and handed over to his deputy, the Biafran Major-General Philip Effiong.

Effiong then made a plea to the Federal Government to tell its troops to stand down, and on January 15, 1970, he officially surrendered to Gowon in Lagos.

The aftermath of the Nigerian Civil War

The Nigerian civil war had a significant impact on the country in terms of human and material resources. It cost the country millions of pounds to fund. The civil war witnessed the death of about 1 to 3 million Nigerians, with the majority being from the Eastern region.

Yakubu Gowon then went on to declare that there had been no winners or losers in the “war of brothers.” According to the head of state, the war was a case of “no victor, no vanquished.”

Over time, the process of reintegration and reconciliation soon began and the Igbos began to spread to several parts of the country, as was the case before the emergence of the civil war. They also had to start from scratch. Those with a bank account were given £20 regardless of whatever amount they had.

Gowon’s victory speech after the civil war did not assuage the animosity of other Nigerians towards the Igbos. Despite being a major ethnic group in the country, they were marginalised from major sectors in the years that followed the civil war. The remnants of that marginalisation are still visible even 52 years after the civil war.

We always have more stories to tell. So, make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button to receive notifications for interesting historical videos. Also, don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and to as well share this article with your friends.

Feel free to join our YouTube membership to enjoy awesome perks. More details here…

Sources

Achebe, C. (2012). There was a country: A personal history of Biafra. The Penguin Press.

Atofarati, A, A. (1992). The Nigerian civil war, causes, strategies, and lessons learnt. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20080312215245/http://www.africamasterweb.com/BiafranWarCauses.html

Daly, S, F, C. (2020). A history of the Republic of Biafra. Cambridge university press. Retrieved from www.cambridge.org/9781108840767

Falode, A. (2011). The Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970: A Revolution? Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228215426

Falola, T. & Heaton, M, M. (2008). A History of Nigeria. Cambridge university press. Retrieved from www.cambrige.org/9780521862943

Hatfield, B. (2019/2020). The Biafran war and its societal ramifications. Der Biafra-Krieg und seine gesellschaftlichen Auswirkungen.

Heerten, L. & Moses, A.D. (2014). The Nigeria-Biafra war: postcolonial conflict and the question of genocide. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14623528.2014.936700

Hurst, R. (2009). Nigerian civil war (1967-1970). Blackpast.org. Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/nigerian-civil-war-1967-1970/

Ibeanu, O.& Orji, N.& Iwuamadi, C, K. (2016). Biafra separatism: Causes, consequences, and remedies. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312129707

Khan, R. & Salim, A. et al. (2021). British Colonialism and the indirect rule: a hierarchical administrative structure to control the unruly tribes. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2021.93136

2 Comments

View CommentsLeave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I love you history lines 💕💕

Interesting!