No products in the cart.

As of the time the officers who carried out Nigeria’s first military coup d’état stopped firing, Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi was the only senior officer of the Nigerian Army High Command who was still alive as of the morning of January 15, 1966.

The General had survived the bloody coup by outwitting his killers. Not only did he escape death, but he also rallied some troops loyal to him and subsequently crushed the coup.

However, Aguiyi-Ironsi would later be killed in a horrible manner six months later in another coup d’état on July 29, 1966.

Contents

Aguiyi-Ironsi: An Early Life

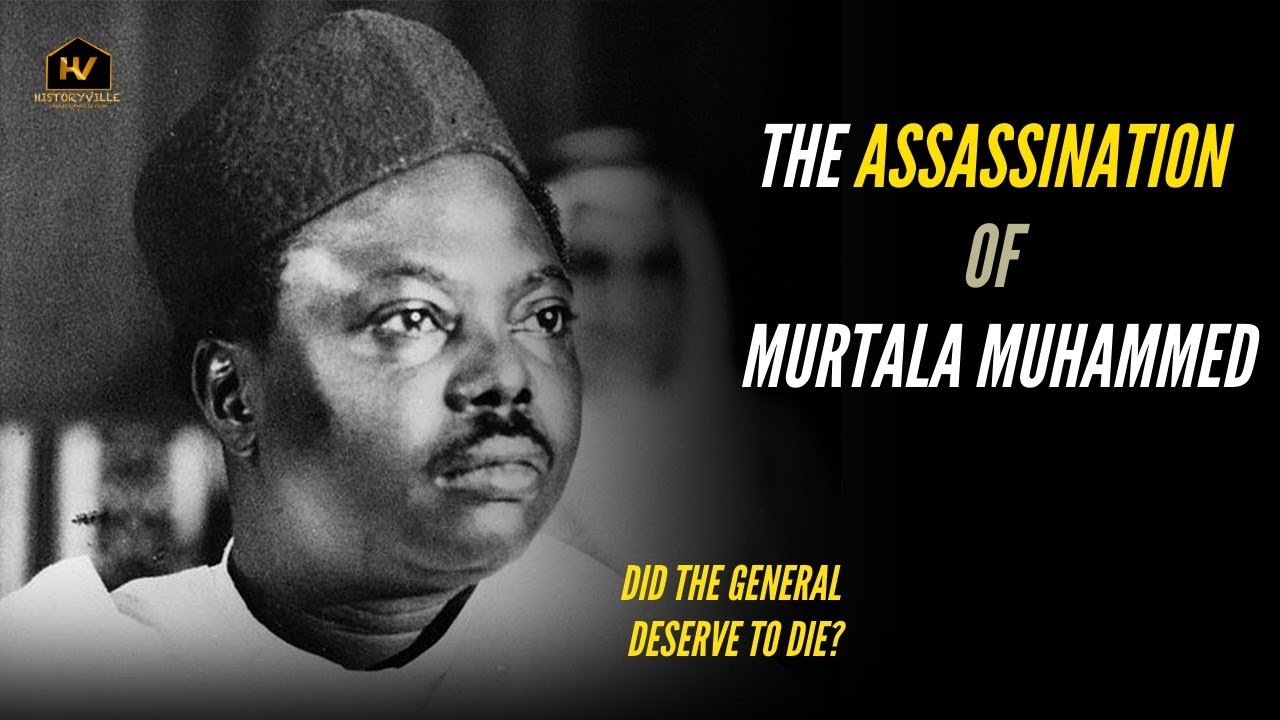

Major-General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi was 41 years, 10 months, and 13 days old when he became Nigeria’s First Military Head of State on January 16, 1966.

Ironsi was born Thomas Umunakwe Aguiyi-Ironsi in Ibeku, Umuahia, the capital of what is now Abia State in Eastern Nigeria, on March 3, 1924. His father, Mazi Ezeugo Aguiyi was an Igbo from Umuahia. The Aguiyi-Ironsi household was a typical Igbo Catholic farming family. Ironsi grew up with his older sister, Anyamma, and her husband, Theophilus Johnson, a Sierra Leonean diplomat working in Umuahia.

The young Ironsi became so ingrained in his new household that he adopted his brother-in-law’s surname, Johnson, as his first name, leading many to believe that Theophilus Johnson was his biological father.

Ironsi went to school at Umuahia, Calabar, and Kano, among other places. He learned Hausa and Yoruba in addition to English and Igbo. At the age of 18, he joined the colonial army and progressed through the ranks to become a company sergeant-major in 1946. Ironsi’s sister did not approve of his decision to join the army.

Life in the Nigerian Army

Following the Second War War, when the British colonial overlords wanted to give over the authority of the new Nigerian army to Nigerians, it became imperative to form a Nigerian officer corps. Ironsi was one of the first groups of decently educated Nigerian Non-Commissioned Officers to be sent abroad for officer training and commissioning.

For the next decade, Ironsi’s career consisted of a series of postings, training, and promotions. The majority of his military education was received in British institutions, all of which have a centuries-old heritage of instilling in their graduates a sense of submission to civilian authority.

Ironsi rose to prominence in 1960, when he was named commander of the Nigerian army’s Fifth Battalion, which was dispatched to the unstable Republic of Congo (previously Zaire) as part of the UN Peacekeeping Force. When the Austrian medical team and the relieving Nigerian soldiers were surrounded by the insurgents, he flew in solo in a light plane and negotiated their release.

For this achievement, the Austrian government awarded him the Ritter Kreuz First Class award.

Ironsi became the first African to command the entire United Nations Force in Congo in 1964. He was the first Nigerian to be promoted to the rank of Major-General. When he returned to Nigeria and assumed command of the First Brigade, he reverted to Brigadier.

In 1965 Aguiyi-Ironsi became the first Nigerian to hold the position of General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Nigerian army. He was promoted to the Major-General rank after succeeding outgoing British Major-General Christopher Welby Everard.

How Ironsi became Nigeria’s First Army Chief

Ironsi’s elevation to GOC was tumultuous, reflecting the shady politics of Nigeria’s ruling class at the time.

Although the Prime Minister and the Defence Minister were responsible for appointing the GOC, General Everard’s recommendation was significant because this was the first time the full command of the Army was being passed to Nigerians, and he had insight into his three most likely successors: Brigadiers Ironsi, Samuel Ademulegun, and Babafemi Ogundipe. Because of his youth and inexperience, he dismissed the fourth, Brigadier Zakaria Maimalari.

Ogundipe was Everard’s recommendation, but the ruling class had other ideas. The dominant Northern People’s Congress, which produced both Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa and the powerful Northern Region Premier, Sardauna Ahmadu Bello, favoured Brigadier Samuel Ademulegun, who was a friend of the latter and appeared more amenable to their political objectives. It was a tense competition.

Ironsi, on the other hand, was uninterested in the army’s separation into camps and stayed out of politics. That would land him the job, owing to his seniority, his stellar record at the United Nations and in the United Kingdom, where he served as Nigeria’s military adviser, and the overwhelming support for Ironsi’s candidacy by the mostly Igbo National Convention of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC), the ruling partner of the NPC.

Despite the fact that Ironsi was well recognised and admired among the Nigerian military circle, some members of the Nigerian Army doubted his abilities. Even Everard, in his recommendations, questioned Ironsi’s competence to be GOC because most of his record-breaking appointments took place outside of Nigeria, and, thus, he was out of touch with the army. The outgoing British General, however, nominated Ironsi for an overseas posting because he was too young to be retired.

Nigeria’s First Military Coup D’état

Meanwhile, as early as January 1965, there were rumors of an impending coup. By August of the same year, the coup plotters led by Majors Emmanuel Ifeajuna and Kaduna Nzeogwu had completed their plans for a Revolutionary Coup, which included the arrest and killings of some top politicians and senior military officers in the country.

Security reports of a coup attempt were forwarded to Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa, who either disregarded them or chose not to act on these reports.

On January 15, 1966, the nation awoke to the terrifying news that Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa had gone missing, though he was later found dead six days later, and that the Sardauna of Sokoto and Premier of the Northern Region, Sir Ahmadu Bello, Premier of the Western Region, Chief Samuel Ladoke Akintola, Minister of Finance, Chief Festus Samuel Okotie-Eboh, and some senior officers of the Nigerian Army had been killed in a military slaughter.

In fact, the Commander of 1 Brigade, Nigerian Army in Kaduna, Brigadier Samuel Ademulegun was shot dead in his singlet while in bed with his pregnant wife, Latifah. Sisi Nurse, as she was fondly called, was also killed with her unborn child while clinging to her dear husband.

The Commander, 2 Brigade Nigerian Army, Apapa, Lagos, Brigadier Zakariya Maimalari, the acting Chief of Army Staff, Army Headquarters, Colonel Kur Mohammed, the Adjutant-General, Lieutenant-Colonel James Yakubu Pam, and the Commander, 4th Battalion, Ibadan, Lieutenant-Colonel Abogo Largema were the fine senior military officers whose careers met a bloody end.

Ademulegun’s deputy, Colonel Ralph Sodeinde was also killed in his bedroom while his wife was shot in the leg. The Quartermaster of the Nigerian Army, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Chinyelu Unegbe was also felled in a hail of bullets in the presence of his pregnant wife.

However, the most senior military officer in the Nigerian Army, Major-General Johnson Thomas Umunnakwe Aguiyi-Ironsi was not killed. He had survived the bloody carnage, as he was also targeted to be gunned down by the coup plotters. As a matter of fact, Ironsi was the only senior officer of the Nigerian Army High Command who was still alive as of the time the killers stopped firing.

Not only did General Ironsi escape death, but he also rallied some troops loyal to the government and subsequently crushed the coup.

So, how was Aguiyi-Ironsi able to escape his killers?

How Major-General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi Escaped Death in the January 1966 Coup D’etat

On the cold, chilly night of Friday, January 14, 1966, at 11, Thompson Avenue, Ikoyi, Lagos, a party was being held for senior military officers of the Nigerian Army. All of the senior officers, along with their ADCs (Aides-de-Camp), were present.

The party was held at Maimalari’s house. The Brigadier was welcoming his new 15-year-old wife from Kano to the south.

Ironsi, as the General Officer Commanding, GOC, of the Nigerian Army, was there. Some senior officers of the Army High Command, who would lose their lives some hours later, were there as well.

The officers, the guests, and everyone present all had a good time. But an hour before midnight, the senior officers left the party, including Ironsi.

But while they left for their homes, Ironsi didn’t. He went to another party.

It was a Friday night. The General was not in a hurry to leave for home. Since Maimalari’s party ended quite early for him, Ironsi left for another party on a ship at the Apapa Wharf.

Now, Aguiyi-Ironsi was a lover of drinks; and being at another party would satisfy his desires for that night.

However, when the mutineers led by Major Donatus Okafor came for the GOC at his house, which is now known as Flagstaff House, the General was conspicuously absent and his guards resisted the soldiers who left with their mission unfulfilled.

When Ironsi returned home from the second party, he received two phone calls alerting him to the ongoing military rebellion in Lagos.

The first was from Pam’s home while the second was the residence of the Prime Minister who had been abducted by Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna, Maimalari’s Chief of Staff.

Swinging into action, Ironsi headed for Ikeja to battle the rebellious soldiers. With the support of Lieutenant-Colonels Hillary Njoku and Yakubu Gowon, Aguiyi-Ironsi’s troops crushed the coup as the rebels fled from Lagos.

Ironsi as Nigeria’s First Military Head of State

These events fueled suspicions among the Northern elite, particularly in the Army, that the Igbos were behind the coup. Ironsi then appointed Gowon, a Northerner, as Chief of Army Staff in an attempt to calm divisions within the army.

The January coup brought to the fore a united Northern Region in the Army, regardless of tribe or religion.

Ironsi’s proclamation of Decree 34 on May 24, 1966, marked the beginning of the end for him. The decree strengthened the centre, thereby removing the powers granted to the regions.

Another blunder made by Ironsi was the failure to prosecute the coup plotters responsible for the January 15, 1966, massacre.

These sparked widespread unrest in the northern part of the country, where residents had been protesting the delimitation of regional powers since 1959. Ironsi began a tour of the country in June 1966, meeting with the Northern elite and assuring them of a united Nigeria.

The July Northern Counter-Coup and Ironsi’s death

On July 28, 1966, the military governor of the Western Region, Lt. Col. Francis Adekunle Fajuyi, hosted the Head of State in Agodi, Ibadan. As Ironsi prepared to leave for Lagos, Fajuyi urged him to spend the night at the Government House in Ibadan.

Northern soldiers led by Major Theophilus Y. Danjuma arrived in the early hours of July 29, 1966, to arrest Ironsi and question him about his alleged complicity in the coup that resulted in the demise of the Sardauna of Sokoto, Ahmadu Bello, and Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.

Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi replied in the negative to Danjuma, denying any involvement in the coup. Ironsi and Fajuyi were eventually overpowered by the soldiers, who violently stripped off their epaulettes. They were also beaten while being dragged to a shallow pit in Lalupon, where their bodies were riddled with bullets.

For three days, Nigeria was without a Head of State, and the most senior northern officer in the army, in this case, Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon, Ironsi’s Chief of Army Staff, was appointed to lead the country.

So, did General Aguiyi-Ironsi deserve to die? Let us know in the comments.

We always have more stories to tell. So, make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button to receive notifications for interesting historical videos. Also, don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and to as well share this article with your friends.

Feel free to join our YouTube membership to enjoy awesome perks. More details here…

Sources

Awoyokun, D. (2020, January 15). 54 Years After: British Secret Files on Nigeria’s First Coup- Part 1. The News Nigeria. Retrieved from https://thenewsnigeria.com.ng/2020/01/15/54-years-after-british-secret-files-on-nigerias-first-coup-part-1/

Iloegbunam, C. (2016, July, 29). July 29, 1966 counter-coup: Africa’s bloodiest coup d’état. The Vanguard. Retrieved from https://www.vanguardngr.com/2016/07/july-291966-counter-coup-africas-bloodiest-coup-detat/amp/

Siollun, M. (2009). Oil, Politics and Violence: Nigeria’s Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). p. 237. New York. Algora Publishing, NY. ISBN: 9780875867106.

Siollun, M. (2005, October 30). “The Inside Story Of Nigeria’s First Military Coup (I)”. iNigerian. Retrieved from https://www.inigerian.com/the-inside-story-of-nigerias-first-military-coup-i/

Siollun, M. (2006, December 7). “The Inside Story Of Nigeria’s First Military Coup (2)”. iNigerian. Retrieved from https://www.inigerian.com/the-inside-story-of-nigerias-first-military-coup-2/

Siollun, M. (n.d). The Northern Counter-coup of 1966: The Full Story. Dawodu. Retrieved from https://dawodu.com/coup2.htm

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

View Comments