No products in the cart.

Did you know the total number of years the British spent in Nigeria as colonial masters? Ninety-nine (99) straight years. Then, it was not officially known as Nigeria.

As of the time the British arrived in 1851, with the bombardment of Lagos, and began colonising the territory now known as Nigeria, 11 years later, the present-day country was made up of different kingdoms and tribes with their languages. They had nothing in common except for their dark skin.

However, on January 1, 1914, the British empowered Lord Frederick Lugard to join the Northern and Southern regions of the country to be known as the Colony of Nigeria and Lagos was chosen as the capital.

Contents

The amalgamation of Nigeria in 1914, carried out without the consent of a majority of these native Africans, was one of the major harms the British did to Nigeria.

We shall also take a look at others in the course of this article. You can watch the video here.

The Genesis of British Influence on Colonial Nigeria

The British Empire ruled colonial Nigeria from the mid-nineteenth century until 1960 when the country gained its independence.

Alongside other European powers, the British Empire had settlements and forts in West Africa in the 1700s but had yet to establish plantation colonies just like what was in existence in the Americas.

In 1807, the British Parliament enacted the Slave Trade Act which prohibited British subjects from participating in the slave trade. This was after over 150 years of rampant trading of slaves by the British and Portuguese, centred on West Central Africa (now the Republic of Congo), the Bight of Benin, which was also known as the Slave Coast with Ouidah and Lagos being the major ports.

Also, Old Calabar (also known as Akwa Akpa), Bonny, and New Calabar were the major ports in the Bight of Biafra.

However, with the enactment of the Slave Trade Act, the British made anti-slavery treaties with powers in West Africa, by using the military to enforce it, and lobbied other European powers to stop the trade.

All of these provided the opportunity for preliminary surveys and research of the region. The economy of the Benin Kingdom which had, hitherto, benefitted greatly from the slave trade, saw a decline and ultimately led to its collapse.

Slavery reduced the region’s otherwise boisterous and rich population leading to chaos and confusion which in turn paved the way for more aggressive colonisation by the British.

The Arrival of Christian Missionaries to Nigeria

Although Christian missionaries had been influential in the abolition of the slave trade, their impact was not felt until the 1840s.

The Church of England’s Church Missionary Society (CMS) was the first mission opened and operated in areas between Lagos and Ibadan while the Roman Catholic religious leaders established missions in the 1860s with the latter being popular among the Igbos while the former was mostly embraced by the Yorubas. The CMS appointed Samuel Ajayi Crowther as the first Anglican Bishop of the Niger and he is credited for translating the English Bible into the Yoruba language.

Nigerians gradually accepted Christianity as the various denominations adapted to local conditions and selected African clerics for the missions.

In the long run, these European missionaries effectively reinforced colonial policy in terms of promoting education, health and welfare schemes and were in control all through the latter part of the 19th century.

On the bright side, they saw an end to inhumane traditional practices such as human sacrifice, infanticide, obnoxious rituals, and so on.

Trade and Commerce

Palm oil and palm kernels which were used to make soap and also serve as lubricants for machinery in Europe were the major commodities traded in Southern Nigeria at the time.

At first, most palm oil and palm kernels came from Igboland where palm trees were in abundance in areas of the Nri Kingdom, Awka, and Ngwa where the palm oil was used for cooking. The kernels were a source of food; palm wine was tapped from the palm trees and the palm fronds served as building materials.

Later on, the Igbos transported the palm oil to rivers and streams along the Niger Delta for sale to the European traders with the British merchants as the major customers. Thus, palm oil was transformed from a subsistence crop to a cash crop as its exports increased greatly.

Calabar and the Niger Delta which had erstwhile been famous for the export of slaves became known for the export of palm oil. ‘Oil Rivers’ was the new name given to the Delta streams.

The economic units in each town were referred to as houses which included the extended family of the trader, servants, and slaves. The trader had a canoe that could contain tons of cargo and crew to defend the harbour.

Hazards of climate, tropical diseases, and non-existent authority on the mainland made European merchants anchor their ships outside harbours where they served as trading stations and warehouses.

Depots were built onshore and moved up the Niger River in order to establish stations in the interior. One of such was at Onitsha where bargaining was done directly with the local suppliers.

Owing to the decline in the slave trade and the hazards accompanying it, many European traders became legitimate businessmen and as the volume of trade increased, the British Government, in 1849, appointed a consul, John Beecroft, to oversee the region which was the Bights of Benin and Biafra.

A Court of Equity was also created by the British in 1850 to settle trade disputes which usually arose among the traders. It was located in Bonny and under the jurisdiction of Beecroft.

Based on an agreement with the local Efik traders, another court was established in Calabar in 1856.

These courts had mainly British members and were thought to be a way for the British to exercise their authority over the Bight of Biafra.

The 1851 Bombardment of Lagos

The Prime Minister of Britain in the mid-19th century, Lord Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, abhorred slavery. Therefore, he took advantage of the presence of Christian missionaries, divisions in native politics and the antics of Beecroft to encourage the end of the slave trade.

In line with an agreement with the deposed Oba of Lagos, Oba Akitoye to help him regain his throne from his nephew, Oba Kosoko, who was a leading slave trader, and abolish the slave trade, the Royal Navy on December 26, 1851, with a flotilla of boats, mounted an attack on the Oba of Lagos’ palace.

Oba Kosoko put up a strong defence but by the second day, the battle, known locally as ‘Ogun Agidingbi’ was won. This event is known as the Bombardment of Lagos.

Consequently, Oba Akitoye was re-installed as the Oba of Lagos and on January 1, 1852, he signed the Treaty between Great Britain and Lagos, thereby abolishing the slave trade.

Having the British consular authority over Lagos led to a rapid increase in trade with the interior in terms of palm oil exports from Lagos and cotton production in Abeokuta.

Despite this, the political situation in the interior had worsened. The British were determined to put an end to the slave trade fuelled by the Yoruba civil wars and this led to the annexation of the Lagos Port in 1861.

Oba Akitoye’s son, Oba Dosunmu, who was now the Oba of Lagos, signed a treaty known as the “Lagos Treaty of Cession on August 6, 1861, with the British Empire. Thus, Lagos was ceded to Britain and became a British Crown Colony.

The colony’s administrator, Captain John Glover formed a militia of Hausa troops and this became the Lagos Constabulary later culminating into the Nigeria Army and the Nigeria Police Force. These soldiers were known as Glover’s Hausas.

In 1891, the Bank of British West Africa was founded in Lagos by the African Banking Corporation.

The Protectorate of Oil Rivers

After the Berlin Conference of 1884/1885, the British announced the formation of the Oil Rivers Protectorate to control and develop trade coming down the Niger River. The Protectorate included the Niger Delta and extended eastward to Calabar.

The territory was renamed the Niger Coast Protectorate in 1894 and, in 1906, was expanded to include the Lagos Colony and northward up the Niger River.

The Royal Niger Company

In the 1870s, a British merchant, George Taubman Goldie merged trading companies located along the Niger River into the United African Company which was soon renamed the National African Company and finally, the Royal Niger Company (RNC).

He did this to bring an end to the fierce competition engaged in by different companies who sometimes used force to get suppliers to go into contract with them and meet their demands.

The Royal Niger Company had its headquarters located at the major trading port of the company which was far inland Lokoja. From there, it took on the responsibility of overseeing the depots along the Niger and Benue Rivers. Sokoto, Gwandu, and Nupe had negotiated treaties with the Royal Niger Company which was seen as giving the company exclusive access to trade as annual tribute was paid in return.

The treaties gave the Royal Niger Company total power to settle whatever disputes arose at the ports, to farm, mine, and build on their territory, to protect the Kings and Chiefs from attacks, and restricted them from interfering with the native laws and customs of the land.

As a result of this, the Royal Niger Company was able to deprive France and Germany of access to the region under Goldie’s command. He was seen as the Founding Father of Nigeria as he was the one who laid the basis for the British claims to the country.

Ultimately, the Royal Niger Company became the sole government of the region, although, the company allowed the local kings to act as partners in governance and trade.

The company employed native workers who were paid in barter. Top earners received four bags of salt per month. Barter and credit were the mechanisms of trade. The major imports of the Royal Niger Company included gin and low-quality firearms.

The Royal Niger Company also had its armed forces, including a river fleet, which were used to attack uncooperative villages.

As expected, Joseph Chamberlain’s appointment as colonial secretary in 1895 brought about a rise in the territorial ambitions of the British Empire.

British colonial rule was being solicited for by local colonial administrators as they believed that trading and taxation done in British pounds would be more lucrative than trade by barter.

British Military Campaigns in Nigeria

To enlarge its sphere of influence, the British led a series of military campaigns and expanded its commercial opportunities. Hausa soldiers were recruited to fight and because the British had superior weapons, tactics and political unity, victory was sure.

In 1892, the British forces overran the Ijebu Kingdom with the Maxim gun. Ijebu had kicked against missionaries and foreign traders; but British machine guns gave them a rollercoaster victory as they swept through the rest of Yorubaland, conquering it, although the area had already been weakened by 16 years of civil war.

By 1893, almost all of the other political entities in Yorubaland had signed diverse treaties with the British, joining them with the Colony of Lagos.

From 1896 to 1897, the forces of the Niger Coast Protectorate fought with the remnants of the Benin Kingdom, captured Benin City and drove Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, the Oba of Benin, into exile.

Conquering Igboland was not a walk in the park for the British as the Igbo people had no central political organisation.

The British launched the Anglo-Aro War of 1901/1902 under the guise of freeing the Igbos from the Aro Confederacy, which was a political union formed by the Aro people. Villages were conquered through the burning of crops and houses but the Igbos remained difficult to subdue. Annual missions with the intent to pacify and convince the locals of British supremacy were carried out by British forces.

Between 1900 and 1903, the British subdued the Muslim-dominated Northern Nigeria with the capture of the Sokoto Caliphate and the Kano Emirates.

Nigeria as a British Colony

By 1897, the British had started their plans for the direct control of the area now known as Nigeria. They agreed that the Colony of Lagos, the Niger Coast Protectorate, and the Royal Niger Company should be merged.

That same year, the Royal West African Frontier Force was created by the British, having Colonel Frederick Lugard in charge. Lugard then recruited 2,600 troops, comprising of both Hausa and Yoruba men evenly split, in one year.

In 1898, The Niger Committee, chaired by the Earl of Selborne, put down guidelines for running the Colony of Nigeria. The border between Nigeria and French West Africa was also finalised with the Anglo-French Convention of the same year.

In 1900, the British Government took control of the Southern and Northern Protectorates which were governed by the Colonial Office at Whitehall.

The Governor-General reported to the Colonial Office and managed his Colony. The seven Governors of the Northern and Southern Protectorates of Nigeria and the Colony of Lagos through 1914 were Frederick Lugard, Henry McCallum, Ralph Moor, Hesketh Bell, William MacGregor, Percy Girouard and Walter Egerton.

The years 1895 to 1900 witnessed the construction of a railway that ran from Lagos to Ibadan and was subsequently opened to the public in 1901. The line was later extended to Osogbo from 1905 to 1907, to Minna and Zungeru from 1908 to 1911 and its final leg enabled it to meet another line being constructed from Baro through Minna to Kano from 1907 to 1911.

Note that the construction of the railway was for the economic interests of the British and not as a means of transportation for the locals. It was constructed to transport raw materials from the North to the Lagos Port and then shipped to industries in the United Kingdom.

The 1914 Amalgamation of Nigeria

As earlier stated, plans to combine the three areas of jurisdiction, that is Northern and Southern Nigeria and the Colony of Lagos had been mulled over and thought to be the solution to reducing administrative expenses and facilitating the easy deployment of money and resources.

In line with the order recommended by the Niger Committee, the Colony of Lagos was merged with the Southern Nigeria Protectorate by the Colonial Office on May 1, 1906.

Lugard constantly advocated for the unification of the whole territory and this task was achieved when Nigeria was amalgamated on January 1, 1914, with the merging of the Southern and Northern Protectorates of Nigeria.

The newly united colony was overseen by a proconsul known as the Governor-General of Nigeria who happened to be Frederick Lugard.

Nigeria was subdivided into Northern, Western, and Eastern regions and a Lieutenant Governor was placed in each region to provide independent government services.

While Hausa was recognised as the official language in the north, English had official status in the South. Economic links were increased among the regions but the indirect rule adopted by the British discouraged political interchange.

Greater unity was not encouraged among the regions until after the end of the Second World War in 1945.

Until the expiration of his tenure as Governor-General in 1919, Lugard was focused on solidifying British sovereignty and assuring local administration through the traditional rulers. As a matter of fact, he spent four months of every year in London and major decisions regarding the country were not carried out until his return. Lugard was scornful of the educated Africans who populated the South, especially Lagos, and recommended that the capital should be transferred from Lagos to Kaduna but his request was rejected by the Colonial Office in London. They argued that such an exercise would be too expensive and unsafe.

However, Lugard’s immediate successor, Sir Hugh Clifford was the polar opposite. An aristocratic professional administrator with liberal instincts who had earlier won recognition for his rulership of the Gold Coast (now Ghana).

Clifford rejected Lugard’s proposal to move the capital from Lagos to Kaduna, clamoured for economic development and encouraged enterprises by immigrant southerners in the north while resisting European participation in capital-intensive activities.

Clifford anticipated general liberation heading to a more representative form of government and building elite schools modelled after European education.

On the one hand, Lugard had wanted to apply lessons learned in the North to the South but on the other hand, Clifford was ready to extend successful practices in the South to the North.

However, the lieutenant-governor in the North, Richmond Palmer, disagreed with Clifford and insisted on using Lugard’s principles and further decentralisation.

The Spanish Flu

In September 1918, the influenza pandemic, popularly known as the Spanish Flu, made its way to the Lagos Port by way of some ships. The spread was quick and deadly, leading to about 1.5% of Lagosians getting affected.

The British colonial government was unprepared and unequipped to deal with the pandemic and an estimated 500,000 Nigerians lost their lives – despite some safety measures, like travel passes, door-to-door checks and enlightenment on sanitary practices, that were put in place.

Taxation and Economy

At first, grants were allocated to the Northern Nigeria Protectorate from the British treasury each year while the Southern Protectorate financed itself. However, after gaining political control of the country, the British introduced a system of taxation.

This was done to encourage wage labour and put subsistence farming in the back seat. Sometimes, forced labour was used for public works projects. These policies were resisted.

In 1906, oil exploration began – with the Colonial Office granting exclusive rights to John Simon Bergheim’s Nigeria Bitumen Corporation. The Corporation received a loan of £25,000 in 1907 which was to be repaid when the oil was discovered.

Bergheim reported striking oil in 1908 and was said to be extracting 2,000 barrels per day in 1909 but the development of the oilfields slowed when he died in a car crash in 1912. A year later, in 1913, Lugard aborted the project.

The British enforced the Native Revenue (Amendment) Ordinance in April 1927 and direct taxation on men was introduced in 1928 without any resistance.

However, while carrying out a census relating to taxation in October 1929 in Oloko, the women in the area were suspicious that direct taxation would be imposed on them and protested. The protest is now known as the Women’s War. They insisted on not paying taxes and not allowing the appraisal of their properties.

The Birth of Nationalism in Southern Nigeria

Nationalism became a political issue in Nigeria as activists sought increased participation in the governmental process. The British tried to preserve the indigenous cultures of each area whilst introducing modern technology, politics and social concepts.

While the North accepted indirect rule, the South opposed it. The southerners’ opposition was due to their educational exposure which they acquired abroad.

These southern nationalists were critical of colonialism and wanted self-government.

Nigerians began to form different associations in the 1920s such as the Nigerian Union of Teachers (NUT) and the Nigerian Produce Traders’ Association led by Obafemi Awolowo. They were centres for educated people to hone their leadership skills and form broad social networks.

Organisations having ethnic and kinship undertones were also formed as tribal unions within the same era. City dwellers who were of the same ethnic groups came together to replicate the lifestyle in the rural areas they came from where everyone looked out for one another.

By the mid-1940s, the Igbo Federal Union and the Egbe Omo Oduduwa, with Awolowo as the leader, had formed their own organisations.

Another type of organisation that was formed was the youth or student groups that were more politically inclined. Newspapers equally provided news on nationalist views.

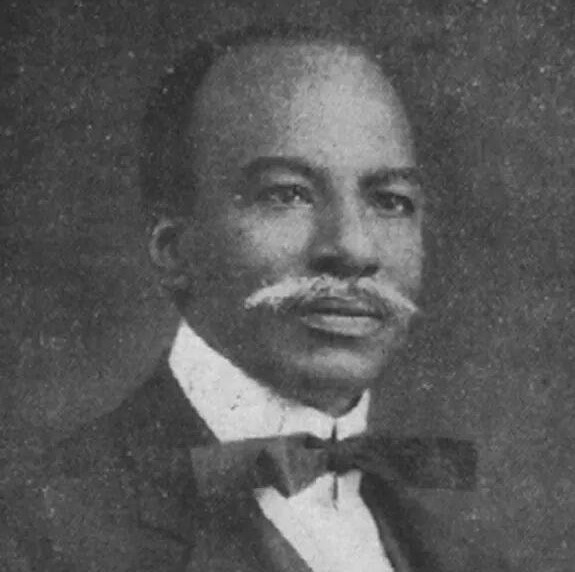

The 1922 Clifford Constitution gave Nigerians the opportunity to vote for several representatives to the Legislative Council with the figurehead being Herbert Macaulay. He is usually referred to as the Father of Nigerian Nationalism.

Macaulay awakened political interest through his newspaper, the Lagos Daily News. He also led Nigeria’s first political party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) which was formed in 1922, to many successful elections in Lagos. Macaulay called for development in terms of the economy, education, Africanisation of the civil service, and self-government for Lagos.

In 1938, the National Youth Movement (NYM) was formed and brought to the fore some future leaders like Nnamdi Azikiwe and Hezekiah Oladipo Davies. The movement agitated for improvement in education and dominion status within the British Commonwealth of Nations for Nigeria to be at par with Canada and Australia.

The NYM ended the domination of the NNDP in the Legislative Council during elections that year; three years later, internal disputes led to the departure of Azikiwe and other Igbo members, leaving the organisation for the Yoruba members.

Awolowo reorganized the NYM into a Yoruba political party and renamed it the Action Group (AG). The Group had a generation of flourishing cultural awareness among the Yoruba and also had valuable connections with interests that were in line with the economic progress of the Western Region.

The Northern People’s Congress (NPC) was organised in the late 1940s with Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, being the most powerful figure in the party. Bello strived to shield northern social and political institutions from southern influences and insisted on maintaining their territorial integrity.

Mallam Aminu Kano, who had been instrumental in founding the NPC, broke away in 1950 to form the Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU). This, he did in protest against the NPC’s narrow objectives and the traditional rulers’ reluctance to accept modernisation.

The political parties tussled for positions of power in readiness for the independence of Nigeria. From 1946 to 1954, three constitutions were enacted which moved the country towards greater internal autonomy even though each one generated political controversy.

Political parties had an increasing role and it all tilted towards the institution of a parliamentary system of government, having regional assemblies and a Federal House of Representatives.

A new constitution formulated by Sir Arthur Richards, who was the Governor-General at the time, was approved in 1946 by the British Parliament at Westminster and promulgated in Nigeria.

The Arthur Richards Constitution reserved power in the hands of the Governor-General but it also provided for an expanded Legislative Council empowered to deliberate on matters affecting the whole country.

Houses of Assembly were established in each of the three regions to advise the Lieutenant-Governors posted there.

However, the Arthur Richards Constitution was suspended in 1950 due to calls for greater autonomy and this led to an inter-parliamentary conference in 1950 at Ibadan. Here, the terms of a new constitution were drafted. It was called the Macpherson Constitution named after the incumbent Governor-General, John Stuart Macpherson and it went into effect in 1951.

The Macpherson Constitution allowed renewed impetus to political activities and participation at the national level and also boosted regionalism.

Subsequent revisions done to the Lyttleton Constitution of 1954, established the federal principle and facilitated independence.

The Road to Self-Governance and Independence

Under the parliamentary system, the Western and the Eastern Regions became self-governing in 1957 and the same was done by the Northern Region two years later.

All the regions stuck to parliamentary forms and were equally autonomous to the federal government at Lagos despite the numerous differences in detail among their regional systems.

Real power was centred in the regions even though at the federal level, specified powers including responsibility for banking, shipping and navigation, communication, currency and external affairs were retained.

Most importantly, the regional governments were in charge of public expenditures obtained from revenues raised within their region.

The major event that had a lasting impact on Nigeria’s economic development was the discovery and exploitation of petroleum deposits. The once-abandoned oil search was revived by Shell and British Petroleum in 1937.

Intense exploration which started in 1946 finally yielded results in 1956 when oil was discovered at Oloibiri in the Niger Delta. The exportation of oil began at facilities constructed at Port Harcourt in 1958.

The House of Representatives election after the adoption of the 1954 Constitution saw the NPC clinch a total of 79 seats with all members from the Northern Region. The National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) took 56 seats while the Action Group grabbed only 27 seats.

The Governor’s Executive Council was merged with the Council of Ministers in 1957 as a step further toward independence and the all-Nigerian Federal Executive Council was formed.

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa who was the federal parliamentary leader of the NPC was appointed Prime Minister. He formed a coalition government inclusive of the Action Group and the NCNC to prepare the country for the final British withdrawal.

For the next three years, Tafawa Balewa was in charge of the country’s internal affairs which he operated with complete autonomy.

Nigeria as an Independent Country

Nigeria became independent on October 1, 1960. Nnamdi Azikiwe emerged as the Governor-General and Head of State while Balewa continued to serve as the Prime Minister and Head of Government.

The government was made up of the popularly elected 312-member House of Representatives and the 44-member Senate chosen by the regional legislatures.

The regional constitutions followed the federal model in terms of functionality and structure.

When Nigeria gained its independence, the prospects appeared promising and expectations for the future of the country were high.

The country had so much going for her. It was the most populous country in Africa, commercial quantities of petroleum had been discovered in the Niger Delta Region in 1958, so the potential for economic growth was great, hence the title, “Giant of Africa”.

Both the country’s citizens and outsiders strongly believed that Nigeria would rise to lead Africa in world affairs. The nation was perceived as a beacon of hope for other colonised nations in Africa that were yet to break free from their masters.

Alas, that dream did not materialise. The country has gone through a series of government upheavals, inter-ethnic wars, a civil war, economic crises, religious conflicts, corrupt leaders, rigged elections, underdevelopment, banditry, and high rates of criminality, to mention a few.

These factors would truncate the Nigerian British parliamentary experiment – as just five years and three months after independence, Nigeria’s First Republic fell on January 15, 1966. You can check out the full story here.

We always have more stories to tell. So, make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button to receive notifications for interesting historical videos. Also, don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and share this article with your friends as.

You can also get A Carnage Before Dawn, a historical account of Nigeria’s first coup d’état. E-book here. Paperback here. And on Amazon Kindle and Amazon Paperback.

Sources

Falola, T. and Heaton, M. (2008). A History of Nigeria. Cambridge University Press. New York.

Lovejoy, P., Cohen, H., Goldman, A., Nafziger, W., Osaghae, E. and Smaldone, J. Library of Congress of the United States. (1991). Nigeria: A Country Study. Library of Congress of the United States, Federal Research Division. Washington, D. C.

Osaghae, E. and Suberu, R. (January 2005). A History of Identities, Violence, and Stability in Nigeria. Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity. No. 6. Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford. UK.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

View Comments