No products in the cart.

On January 3, 1949, Oba Samuel Ladapo Ademola (1872–1962 ) the 7th Alake of Egbaland (1920–1962), abdicated the throne due to strife with Egba women, led by Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (1900-1978) and her sister-in-law, Eniola Soyinka, mother of Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka (b. 1934), on the issue of tax. The women were made to pay heavy taxes and were also maltreated.

After days, months, and years of protest, the Alake, who was regarded as a stooge of the colonial master, was removed and forced out of the palace and had to move to Ogbomoso (other records say Oshogbo) where he stayed until December 1950 before things came back to normal.

The intrigues, thrills, and frills of this event are the focus of this article. First, who was Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti?

Contents

Biography of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti

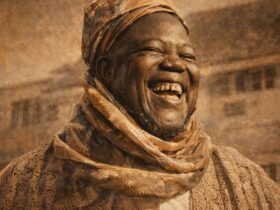

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was born Francis Abigail Olufunmilayo Thomas to Daniel Olumuyewa Thomas and Lucretia Phyllis Omoyeni Adeosolu, on October 25, 1900. She was a teacher, political campaigner, women’s rights activist, and traditional aristocrat.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti served with distinction as one of the most prominent leaders of her generation. She was also the first woman in Nigeria to drive a car.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti’s political activism led to her being described as the doyen of female rights in Nigeria, as well as to her being regarded as “The Mother of Africa“.

Early on, she was a very powerful force advocating for the Nigerian woman’s right to vote. Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was described in 1947, by the West African Pilot as the “Lioness of Lisabi” for her leadership of the women of the Egba clan that she belonged to, on a campaign against their arbitrary taxation. That struggle led to the abdication of the Egba high king Oba Ademola II in 1949.

Education, Marriage, and Family

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was raised by parents who valued education and became the first girl-student admitted to Abeokuta Grammar School, hence, her nickname–Beere (which means a first girl in Yoruba). She later went to England for further studies. She soon returned to Nigeria and became a teacher.

On January 20, 1925, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti married the Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti (1891–1955). He also defended the commoners of his country and was one of the founders of both the Nigeria Union of Teachers and of the Nigerian Union of Students. The marriage was blessed with four children; Olikoye, Bekolari, Olufela, and a girl, Oludolapo.

Indirect Rule in Abeokuta

In 1918, Governor-General Frederick Lugard had introduced a system of direct taxation and created the Sole Native Authority which was a form of indirect rule whereby the traditional rulers acted as agents for the colonial government.

The Sole Native Authority (equivalent to today’s Local Government) was headed by the Alake. It had far-reaching powers and all the previous checks and balances on the power of the Alake was eroded under the indirect rule system as kingmakers, chiefs, and priests who could act to limit the abuse of power of the Alake were now dependent on the Sole Native Authority for their appointment to advisory councils. In plain words, they were rendered effeminate.

Before the advent of the British, women had participated in politics and had their own representatives. The most important was the Iyalode on state councils whose duty was to protect and promote women’s interest.

When they (the British) came, it never occurred to them that women had any significant role and so they never made any provision for it. Nevertheless, some women titles like Iyalode and Erelu remained but they lacked power and influence.

Political Limelight

The aching issue for the Egba women was taxation. Having been subjected to tax by the colonial government, they provided as much as one-half of district revenues. Yet, they had no direct representation on the Sole Native Authority council, a situation they abhorred so much.

Further, the manner by which taxes were collected was often through insult, violence, chasing of women, beatings, and stripping of young women ostensibly to assess their age.

As time went on, complaints increased, reaching a point where women decided that their only chance to gain redress of their grievances was a more militant approach. They considered the tax as foreign, unfair, and excessive. They also objected to the method of collection.

This was the one issue that catapulted Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti into the political limelight, first in Abeokuta, and then in Nigeria.

Abeokuta Women’s Union

In 1923, she (Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti) had organised a group of young girls and women into the Abeokuta Ladies Club. The group was made up of a western-educated middle class and mostly Christian women who concentrated on crafts and social etiquette.

Around 1943/1944, the Abeokuta Ladies Club regrouped and expanded to include market women who had approached Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti to explain their ordeal to her. Most of these women were uneducated and it was at this point that Kuti began her political activism which aimed at raising the standard of womanhood in Abeokuta, encouraging learning among the adults and thereby wiping out illiteracy.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was appalled to hear of the level of exploitation by the colonial and Egba Native Authority, and harassment by police and representatives of the Alake against women. She discovered that the Alake, the traditional ruler of Abeokuta was diverting confiscated rice to his own stores, selling it and pocketing the profits (the rice had been confiscated by the government from women traders).

In 1946, the burden of taxation became unbearable and the Abeokuta Ladies Club metamorphosed into the Abeokuta Women’s Union. This was designed to challenge both colonial rule and the male-controlled structure. Through the union, they opposed price controls and the imposition of direct taxation, engaged in press campaigns, and mobilized so much pressure against the Alake.

The Fight with the Alake

The Abeokuta Women’s Union was a well-organised and disciplined organisation. Mass refusal to pay the tax combined with an enormous protest led to a brutal response from the authorities as tear gas was deployed and beatings were administered.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti ran training sessions on how to deal with this threat, teaching women how to protect themselves from the effects of tear gas and how long they had to throw the canisters back to the authorities.

In late 1946, the Alake increased the tax rate for women. Thousands of women marched to the palace to protest these increases. The Alake’s only response was that if any woman felt her taxes were too high, she should appeal to him individually.

It seemed there was nothing to achieve, so the Abeokuta Women’s Union, through their leader, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, engaging in a tremendous letter-writing effort, outlined the women’s grievances to newspapers in Lagos and Abeokuta.

A mass movement was organised and they laid down objectives, some of which included:

- Resistance against the poll tax

- Resistance against harsh enforcement of sanitation regulations, the payment of water rate, and

- The removal of the Alake from office.

The Alake was vigorously criticised since he was considered the personification and symbol of the Sole Native Authority to the detriment of his people’s well-being.

Although the colonial government was the real source of power, the Abeokuta Women’s Union attacked its agents, the Sole Native Authority and the Alake. They challenged the Alake’s abuses of food and price controls, his interference in trade and court matters. He was also charged for demanding sex from some women who had left their abusive spouses to take refuge in his palace and charging them for accommodation.

In addition, the Abeokuta Women’s Union called for the representation of women in all bodies that administered Egba affairs by members of the union. Their rationale was that since the men had not protected their rights, women’s representatives were needed to do so. The anti-tax protest was a long one with Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti at the head leading the women in the struggle.

In 1947, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti refused to pay her taxes and was arrested. At her arraignment where she pleaded “not guilty”, thousands of women congregated at the courthouse to demonstrate their support. The next year, she again refused to pay her taxes. She led the Abeokuta Women’s Union in laying down plans for a systematic programme of mass protest.

The first major demonstration was held on November 29 and 30, 1947. Many women took part. As they neared the Alake’s palace, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti commanded the marchers to stop, closed her eyes, and told them that all those who were afraid should leave while her eyes were closed. None withdrew. They maintained vigil during which they sang abusive songs.

The Vengeance-Seeking Vagina

In reference to the Aba Women’s Riots of 1929, the women were careful to stress the importance of not allowing the authorities any excuse to attack them or use violence by making sure no weapon was carried. Many women were jailed but were later released.

In January 1948, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was banned from the palace for insulting the Alake and the British administration supported it. Administrative attempts to woo away the Abeokuta Women’s Union executive from its support of Kuti failed. They also refused to attend any meetings without Kuti.

By April, the women were determined to get rid of the Alake and obtain their demands, one of which included that the Alake be removed from office. They continued their demonstration and vowed to go on the streets in nudity (a taboo in Egbaland).

As they got to the palace, they blocked the two main colonial officers, the Resident and the District Officer, from leaving the palace.

As they protested, led by Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, they sang in Yoruba:

“Alake, for a long time you have used your penis as a mark of authority that you are our husband. Today, we shall reverse the order and use our vagina to play the role of a husband on you. O you former men conquerors, the head of the vagina has sought vengeance..”

The Abdication of the Alake

To gain time, the Alake decided to go for a holiday at the beginning of June in Jos, hoping things would cool off in his absence. He appointed a special committee to investigate the complaints of the women. He also suspended their taxation and agreed to a women-representative on the central committee.

Alas, the women were no longer interested in anything he did. They were only interested in his abdication, so they continued their demonstrations.

After he returned, he ceded further ground by resigning from his position as Sole Native Authority. But the women would not budge and blatantly refused to accept anything less than his total abdication and continued their demonstrations.

In July, the Egba chiefs and members of the Egba Native Authority passed a resolution against the Sole Native Authority system. They also charged the Alake with corruption and abuse of power. They thereby rejected him as king, rang the bell, and beat the traditional drums to that effect.

Finally, on January 3, 1949, the Alake abdicated. The women’s protest which had intensified from October 1946 to July 1948 had been successful. Four women, all executive of the Abeokuta Women’s Union, including Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti were appointed to the Egba Central Council that replaced the Sole Native Authority and the women’s taxation was also abolished.

What happened to the Alake?

Certainly, Oba Ademola had attracted considerable opposition for his misuse of power in the course of his long reign of 28 years. However, there remained a powerful group of loyalists who were committed to the Alake. This group launched a vigorous campaign against his abdication and against the selection of another monarch in his stead.

Chief Kusimo, the Oluwo of Ake, and Chief Adeliyi, the Ashipa of Egba, led other chiefs to disclaim the resolution of the Central Council that the government should not allow the return of the Alake. The chiefs also did not accept the resolution reportedly signed by 10,000 Egba citizens as credible or authentic. They ultimately achieved the reinstatement of the king after nearly two years in exile.

After this episode, the embattled Alake was welcomed back and, thereafter, he ruled with wider support and became the senior in order of precedence in the Western House of Chiefs.

Despite the glaring abuses against the Alake and the desire of the Egba people to elect a new Alake, British colonial officials, in connivance with ethnopolitical entrepreneurs, returned him to the throne secretly in December 1950, without the necessary mandate.

Oba Sir Samuel Ladapo Ademola II would rule for 12 more years until he joined his ancestors in 1962. He remains the longest-reigning Alake to this day.

One of his children by his marriage to Tejumade Alakija, a sister of the famous Adeyemo and Olayinka Alakija, was Sir Adetokunbo Ademola, the first indigenous Chief Justice of Nigeria.

All’s Well That Ends Well

As a result of the success of the Abeokuta’s Women Union, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti decided to expand its organisational structure on a trans-ethnic and trans-regional basis changing its name to the Nigerian Women’s Union (NWU), as branches were opened in Aba, Benin, Calabar, Enugu, Ibadan, Kano, and Lagos.

The Union continued to operate literacy classes in addition to maternity and child welfare classes. However, it remained a special-interest group and did not attempt to engage in overtly political action on a national scale.

If you liked this article, subscribe to our YouTube Channel for interesting historical videos and follow us on all our social media handles. Don’t hesitate to, as well, share this article with your friends.

You can also get A Carnage before Dawn, a historical account of Nigeria’s first coup d’état here.

Details of a story read in brief earlier. A good job.