No products in the cart.

On January 1, 1973, the Nigerian Naira was introduced. The new currency replaced the Nigerian pound with an exchange rate of ₦2 to £1 in the United Kingdom and ₦1 to $0.6 (60 cents) in the United States of America. However, as of today, £1 exchanges for ₦547.59 while $1 exchanges for ₦415.84 at the interbank. These rates are much higher in the black market.

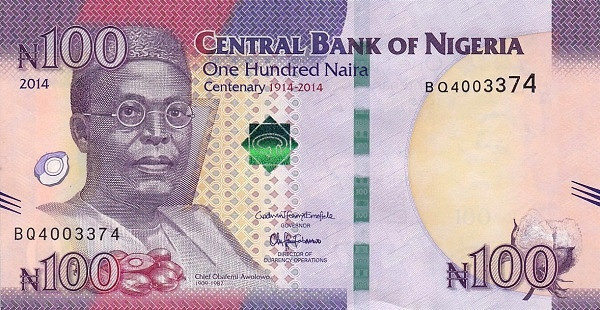

It was Chief Obafemi Awolowo (1909-1987) who, as Nigeria’s Federal Commissioner of Finance, coined the name “Naira”, by collapsing the word “Nigeria”, and “Kobo”, a corruption of the word “copper” because coins were then made of copper. Awolowo’s portrait adorns the ₦100 note.

In this article, we shall take a look at the history and evolution of the Nigerian naira. You can watch the video here.

Contents

The advent of the Nigerian Naira

Before Nigeria was colonized by the British, the means of exchange were cowries, beads, bottles, farm produce, and so on.

Shillings and pence were introduced as the legal tender currency in British West Africa in 1880. The unit of coins managed by the Bank of England was one shilling, one penny, ½ penny, and 1/10 penny which were distributed by the Bank for British West Africa till 1912.

The West African Currency Board (WACB) issued the first set of banknotes and coins in Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia from 1912 to 1959 with one pound being the highest banknote denomination and one shilling being the highest coin denomination.

However, on July 1, 1959, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) began issuing Nigerian currency banknotes and the WACB issued banknotes, and coins were phased out. This continued until July 1, 1962, when the currency was changed to reflect the country’s republic status and the banknotes had FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA inscribed at the top from the previous inscription of “Federation of Nigeria”. The notes were changed again following the misuse of the banknotes during the Nigerian civil war.

Before the government decided to change from metric to decimal, of which Nigeria was the last former British colony to do so, the name of the Nigerian currency was changed on January 1, 1973. The major unit of currency which used to be £1 ceased to exist and the one naira which was equal to 10 shillings, became the major unit while the kobo became the minor unit, a hundred kobo making one naira.

As earlier stated, the name “naira” was coined from the word “Nigeria” by the then Federal Commissioner of Finance, Chief Obafemi Awolowo while “kobo” is derived from the English word, “copper” because coins were then made of copper.

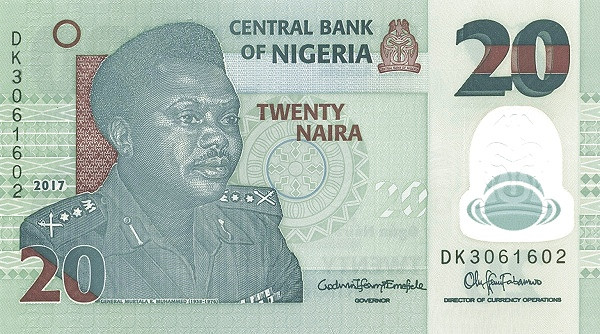

Subsequently, on February 11, 1977, a new banknote (₦20) was issued. This was the highest denomination at that time and it was introduced as a result of the economic growth and the need for cash transactions. It was also the first banknote to have the portrait of a prominent citizen of Nigeria on it – the murdered Head of State, General Murtala Ramat Muhammed (1938-1976).

The ₦20 note was issued on the first anniversary of his assassination as a tribute to him and he was declared a national hero on October 1, 1978. Interestingly, the ₦20 note remains the only naira to have a portrait of a military man. The rest of the naira notes bear the portraits of civilians.

Thereafter, new currency banknotes of three denominations, ₦1, ₦5, and ₦10 were introduced on July 2, 1979. They were of the same size as the ₦20 note which is 151 x 78. To differentiate the denominations, different colors were used to identify them.

Just like the ₦20, these new notes also bore the portrait of prominent men. The ₦1 note featured Nigerian politician, Herbert Macaulay (1864-1946), the ₦5 note has Nigeria’s first and only Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa’s (1912-1966) portrait on it, and the ₦10 note bears the portrait of Nigerian Statesman, Alvan Ikoku (1900-1971) on it. They were all declared national heroes on October 1, 1978.

For easy identification, different colors were used for the various denominations. Also, distinct cultural aspects of the country were engraved on the back of the notes.

However, in April 1984, during the regime of Major-General Muhammadu Buhari, all but one of the colors of the banknotes were changed (the 50 kobo) to curb currency trafficking which was rampant at the time, and in 1991, the 50k and ₦1 were changed to coins.

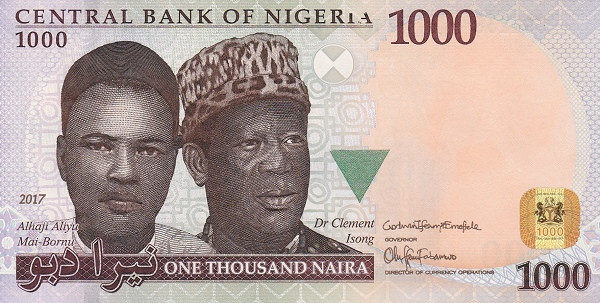

Due to the expansion in economic activities and to create an efficient payment system, the ₦100 (December 1999), ₦200 (November 2000), ₦500 (April 2001), and ₦1000 (October 2005) banknotes were later introduced.

As part of economic reforms, on February 28, 2007, the ₦20 banknote was issued for the first time in a polymer substrate, which is more durable than paper by not becoming soaked in liquids, and is harder to counterfeit, though not impossible.

Also, the ₦50, ₦10, and ₦5 banknotes, as well as the ₦1 and 50k coins, were reissued in new designs along with the introduction of the ₦2 coin.

Following the successful performance of the ₦20 banknote, ₦50, ₦10, and ₦5 were converted to polymer substrate on September 30, 2009.

Finally, as part of its contribution towards Nigeria’s 50th-anniversary independence celebration and the country’s 100 years of being in existence, the CBN issued a ₦50 Commemorative polymer substrate banknote on September 29, 2010, and the ₦100 Commemorative banknote on December 19, 2014, respectively.

The Relevance of the Naira

Nigeria’s monetary system mirrors her history, colonization, struggle, and strength. The naira is more than just a medium of exchange; it also represents the face, people, and culture of the nation. More than being a legal tender, the naira is a bridge-builder between local and foreign borderlines (in terms of local and international trade).

This means that the naira banknotes were not designed as an afterthought but had a clear vision and mission of bridging the gap across cultures and uniting the nation. For instance, the ₦50 banknote is also known as the “WaZoBia note. It portrays the three major ethnic groups in Nigeria, Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba, saying “come” in their respective languages.

Not forgetting that all the banknotes either have the portraits of different notable figures in Nigeria or some aspects of the country’s culture portrayed on them, which goes a long way to show that the naira seeks to bring the different tribes under one umbrella.

With this currency, the Nigerian people all speak the same language and the naira can be said to be an essential symbol of the country’s nationalism and pride.

The Evolution of the Naira

Four decades ago, one could get less than ₦6.1 million in exchange for $10 million. Then, a dollar was equivalent to 61 kobo. The same cannot be said four decades after as the naira has lost 99.8% of its value against the dollar, going by how ₦4.1 billion now exchanges for $10 million.

The naira has witnessed dozens of devaluations, most of which were implemented for the purpose of achieving fair value for the value. In March 2020, the Central Bank of Nigeria adjusted the official rate from ₦307/$ to ₦360/$. The exchange rate was reduced to ₦380/$ later that year.

That rate held out until 2021 when the CBN’s official rate was replaced with the Investors’ and Exporters’ (I & E) Window rate which is a creation of the currency crisis itself.

From the 1980s to this day, the CBN has experimented with all known currency management approaches while the naira kept wobbling against its peers, even within Africa.

The revaluation was contemplated by the apex bank under Prof. Charles Soludo’s tenure as the Governor, which was a proposal meant to strike out two zeroes from a denomination and revert the currency to its heydays. For instance, a ₦500 banknote was to be revalued as ₦5 but political intrigues trailed its implementation.

Factors that have crippled the Naira

Many Nigerians have traced the historical downturn of the naira to the ill-conceived infamous Structural Adjustment Policy (SAP), which is a set of economic reforms that a country must adhere to in order to secure a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the World Bank. Such adjustments could include reducing government spending, opening to free trade, currency devaluation, and so on. It can provide the political will to take necessary and difficult steps to deal with an economic crisis and provide a framework for long-term growth and stability.

Unfortunately, the naira indeed jumped from 89k to a dollar in 1985 to ₦4/$ in the latter days of the SAP and as typical of the IMF and World Bank, certain conditions were demanded among which was the adjustment of the exchange rate, to approve facilities for Nigeria.

Since then, the naira has been on a roller coaster with several liquidity crises in-between and each year witnessing a call for devaluation. Still, the naira is considered overpriced.

Truth be told, the strength of a currency is determined by interrelationship among certain factors like demand and supply, the volume of exports compared to imports and performance, and the competitiveness of the domestic economy.

Although a stronger currency doesn’t produce a stronger economy, a stronger economy will always produce a stronger currency. This goes without saying that a weaker currency is better for an economy that wants to be competitive in the international market.

However, the naira has lost over 99 percent of its value against the dollar in the last 40 years and there are other entrenched challenges such as insecurity, poor local input sourcing, logistics challenges, and so on, that a weaker naira cannot address.

Ever since the Bretton Woods settlement of 1944, the world’s reserve currency has been the dollar and in 1973, United States Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, in exchange for American military protection, reached an agreement with the House of Saud to make the dollar have a sole monopoly as the currency for international oil trading.

The value of Nigeria’s currency is shaped by several factors, one of which is inflation. In the words of American economist, Murray Rothbard, “inflation not only raises prices and destroys the value of the currency unit, but it also acts as a giant system of expropriation”. Inflation weakens the currency against those of competitors.

Another factor that has shaped the naira is the total number of international trade transactions, that is, imports, exports, and debts which stands for the current account balance of the country. A positive account balance strengthens the exchange rate while a negative one weakens it.

Third, Nigeria’s current debt which stands at ₦38.005 trillion, has put the naira in a bad shape.

The next factor is the ratio of export prices to import prices which, if the prices of Nigeria’s exports are rising faster than those of its imports, the naira would be strengthened. The reverse has been the case because while oil prices keep heading south, prices of industrial manufacturing have been heading north.

Last of all, Nigeria has experienced two major recessions in five years. The first, from 2015 to 2017, was triggered by a fall in oil prices, and the second, from 2019 to 2020, was due to the coronavirus pandemic. These events grossly crippled the naira.

Technically, there are so many other factors that can be attributed to the present state of the naira such as political instability and visionless leadership, dollarisation, poor monetary policies, currency speculation, and so on.

A Brief History of the Rise and Fall of the Naira

Nigeria’s currency relationship with other foreign currencies has been erratic, unpredictable, and heartbreaking. Now, let us take a look at how the naira has fared since its introduction.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the naira exchanged at a rate of 90k/$1. Nigeria’s Head of State, General Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida then introduced Second-Tier Foreign Exchange Market (SFEM) as part of a package of IMF reforms. But by the time his inglorious regime ended on August 26, 1993, the naira was exchanging for ₦17/$1. It was during this time that the now popular “Bureau de Change” was introduced.

Throughout General Sani Abacha’s military regime (1993-1998), the official exchange rate of the naira to the dollar was stable at ₦22/$1 but the market rate was ₦88/$1. The CBN introduced the Autonomous Foreign Exchange Market (AFEM) in 1995 in order to sell forex to end-users at market rates. A lot of banking fortunes were made from this arbitrage.

When Joseph Sanusi became the CBN Governor in 1999, he introduced the Interbank Foreign Exchange Market (IFEM). At this time, Nigeria’s reserves had been severely depleted two years before he became Governor and it was his solution to rescue the naira. The naira started trading at ₦85 within a year and the gap between the official rate and market rate had reduced considerably to ₦105/$1 compared to how it was under Abacha.

Sanusi later suspended the IFEM for six months when the naira came under pressure and he introduced a limit to the margin which is above CBN’s rate, that banks could sell their own forex for. The same is being done by the current CBN Governor, Godwin Emefiele.

Previously, Nigeria had been struggling to service its $33 billion foreign debt and also had low oil prices to contend with but as oil prices rose, the country acquired $18 billion debt relief from the Paris Club, and forex round-tripping games blossomed. New generation banks sprouted on a daily basis and set up foreign entities to help their clients move money abroad.

In 2004, rising oil prices increased Nigeria’s foreign reserves and also the Excess Crude Account. The CBN Governor Charles Chukwuma Soludo was able to harmonize the four different rates at the time, which were the CBN, Interbank, Bureau de Change, and wire rates. This converged the rates to within ₦1 of each other. Nigeria was overflowing with dollars. Also, during this period, the naira was strengthened against the dollar by about 20 percent without anyone’s effort.

Unfortunately, oil prices started to drop but Nigeria luckily had her reserves. Despite this, Soludo created an artificial scarcity of forex to allow a devaluation of the naira and also banned the Interbank market for six months.

His successor, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, in 2009, then restored the Interbank market that Soludo had banned due to the rise in oil prices but faced stagnancy in Nigeria’s reserves due to scarcity of dollars to defend the naira. His solution to the problem was to remove the one-year restriction on foreign investors who wanted to buy government bonds.

This move saw Nigeria being included in JP Morgan’s index. Oil prices remained high during Sanusi’s tenure and the naira experienced stability somewhat, starting at ₦148/$1 at the start of his tenure in 2009 and ₦164/$1 in 2014 when he was suspended. Sanusi remains the only CBN governor to have been suspended by then-President Goodluck Jonathan.

In today’s economy, revenues have dropped much more than oil prices. Nigeria’s overdependence on oil is slowly killing the economy. What is even worse is Nigeria did not save during the oil boom and her reserves are probably less than the declared $30 billion.

Current CBN Governor, Godwin Emefiele has banned the Interbank forex market and some items from being eligible for forex. CBN now rations forex and decides who gets what.

The e-Naira

On Monday, October 25, 2021, President Muhammadu Buhari launched the e-Naira – a digital currency produced by the Central Bank of Nigeria that provides a unique type of money denominated in Naira.

As opposed to cash payments, the e-Naira acts as both a means of exchange and a store of value, providing better payment prospects in retail transactions. The e-Naira, according to the apex bank, also has a unique operational structure that sets it apart from other forms of central bank money.

We always have more stories to tell. So, make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button to receive notifications for interesting historical videos. Also, don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and to as well share this article with your friends.

Feel free to join our YouTube membership to enjoy awesome perks. More details here…

Sources

Central Bank of Nigeria. (n.d.) History of Nigerian Currency. Central Bank of Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.cbn.gov.ng/currency/historycur.asp

Fawenhimi, F. (2015, December 6). A (not so) brief history of the fall and fall of the Nigerian naira. Quartz Africa. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/564513/a-not-so-brief-history-of-the-fall-and-fall-of-the-nigerian-naira/amp/

Iyatse, G. (2021, October 18). Osinbajo’s prescription and painful history of naira devaluation. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/business-services/osinbajos-prescription-and-painful-history-of-naira-devaluation/

Kedem, S. (2021, October 28). Nigeria launches eNaira – Africa’s first digital currency. African Business. Retrieved from https://african.business/2021/10/finance-services/nigeria-gears-up-for-enaira/

Mailafia, O. (2021, August 9). Decline and fall of the Naira. Vanguard. Retrieved from https://www.vanguardngr.com/2021/08/decline-and-fall-of-the-naira/amp/

The Guardian. (2016, October 1). The Evolution of Our Currency. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/life/culture-lifestyle/the-evolution-of-our-currency/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

View Comments