No products in the cart.

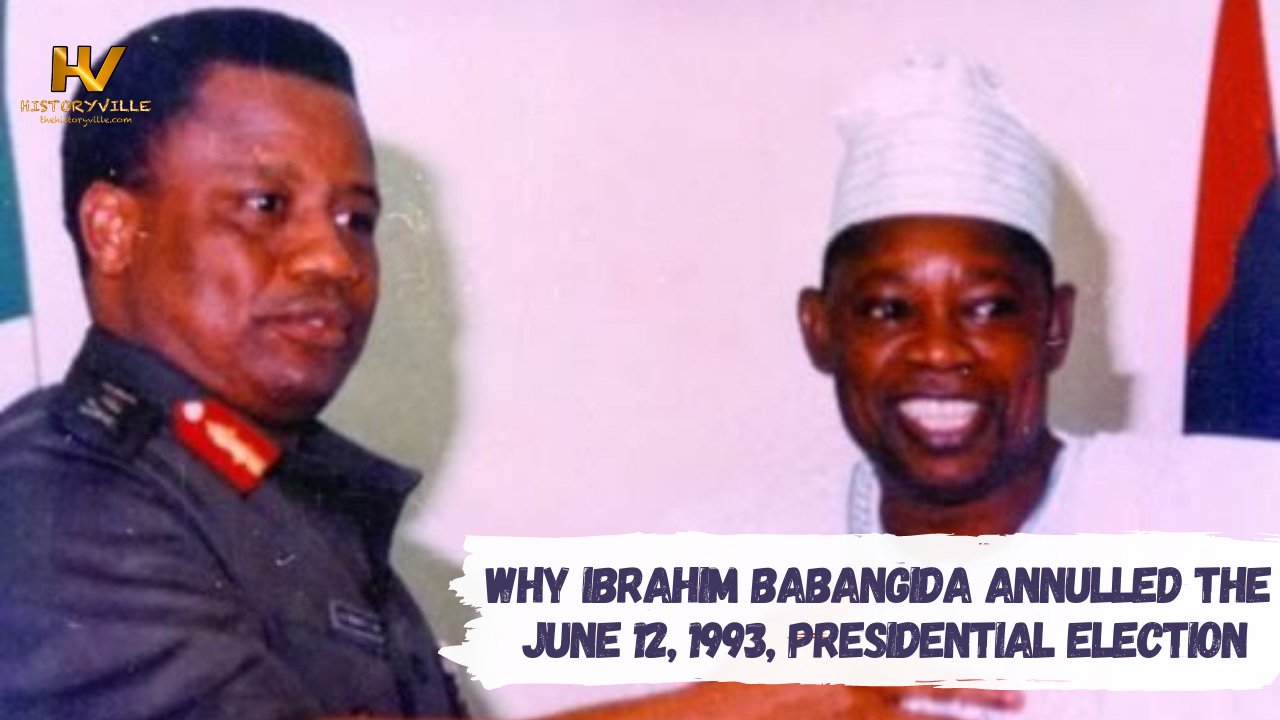

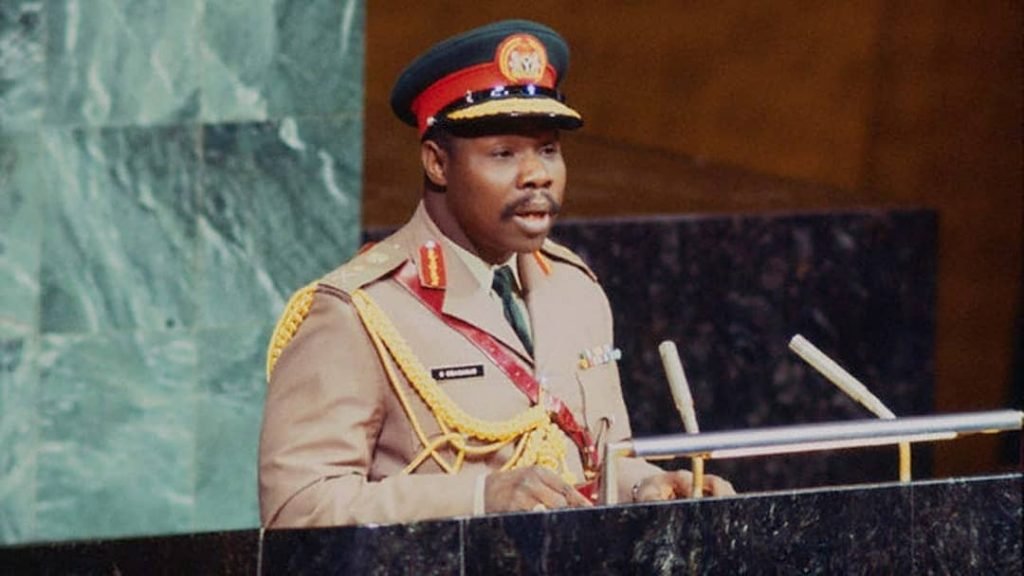

The June 12, 1993, presidential election should have ended with Nigerians celebrating the end of another military dictatorship. Instead, the citizens were faced with a new and more dangerous phase of military rule as Nigerian Head of State, General Ibrahim Babangida and his cronies, in a flimsy attempt to disguise the continuation of their regime, annulled the elections, implemented a so-called interim national government, and postponed the military’s exit from politics.

Babangida’s manoeuvrings did not only betray the Nigerian voters, who in the June 12, 1993, presidential elections had overcome ethnic, religious and regional rivalries in an effort to rid themselves of military rule, but, tragically, brought such rivalries back to the political foreground.

The intention of General Babangida and his allies to disallow civilians a significant voice in government was proven by the brutal reaction of his military and security forces to the outcry which followed the election’s annulment.

Contents

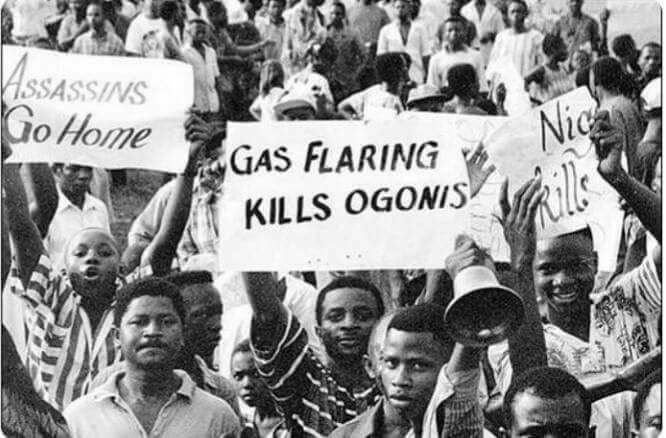

One month after the annulment in July 1993, over a hundred demonstrators were believed to have died in pro-democracy demonstrations. Hundreds of human rights and pro-democracy activists, labour leaders, journalists, students, and workers were arrested in months to follow, without access to their families, defence counsel or doctors, despite court orders granting their release on bail.

Media houses were proscribed, a number of journalists were detained while some were declared wanted by security agents. New restrictive press regulations were decreed, thereby reneging on the promise he made in August 1985 after sacking the Muhammadu Buhari regime.

In this article, we shall take a look at the events that led to the June 12, 1993, presidential election, why General Ibrahim Babangida annulled the elections, the aftermath of the annulment, and the causes and effects of the June 12 crisis.

What led to the June 12, 1993, Presidential Election?

Nigeria is made up of more than 250 ethnic groups, the three largest of which are the Hausa-Fulani, who make up the bulk of the population in the northern region, the Yoruba, who form the majority in the southwest, and the Igbo, who are the largest group in the east. The Hausa-Fulani are mainly Muslim and have traditionally controlled Nigerian politics.

The Yoruba and Igbo, who dominate the southern regions, are largely Christian. Ethnic, religious, and regional conflicts have been a constant factor in Nigerian politics, especially during the civil war which broke out in 1967 and claimed over a million lives.

As of 1993, Nigeria had enjoyed civilian rule for only 10 of its 33 years of independence and no Southerner had ever held office as an elected president.

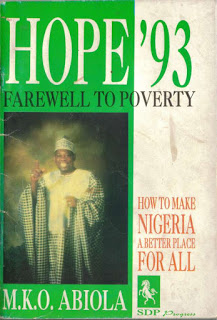

The June 12, 1993, presidential election in which a southern Muslim, Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola won a majority of the vote in all regions of the country, represented a break with past traditions of ethnic, religious, and regional conflicts and all too briefly raised hopes for unifying the nation to confront the serious economic and social problems that have grown more severe under decades of military rule.

After he seized power in a palace coup on August 27, 1985, General Ibrahim Babangida, through the combined effects of a barrage of military decrees, the brutal behaviour of security forces, a disregard for the rule of law, and repeated attacks on civil institutions brought Nigeria to the brink of ruin.

In the period leading up to the June 12, 1993, presidential election, many Nigerians were not optimistic that the new civilian government would represent a significant change. The transition programme, since its inception in 1987, had been tightly controlled by the government, which created and manipulated the two parties contesting the presidency – the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the National Republican Convention (NRC).

At election time, the two presidential candidates, Bashir Tofa of the NRC and Moshood Abiola of the SDP, were both widely perceived to be close friends of the military who would be unwilling to alter the status quo.

Tofa, a Fulani millionaire businessman from Kano State, was relatively unknown to voters. Abiola, a Yoruba Muslim from Abeokuta, is Nigeria’s best-known millionaire and philanthropist. In the final days of the campaign, he had sought to distance himself from the military’s unpopular policies. Despite the general lack of faith in the new civilian government, the elections were believed to represent a crucial step in the nation’s moves toward democracy.

In the months leading up to the elections, many Nigerians believed that the military would find another excuse to cling to power because the government chose the symbols of these parties, wrote their party platforms, and banned candidates it found unfit.

Another reason for their scepticism was a campaign by the Association for a Better Nigeria (ABN), a shadowy group headed by Arthur Nzeribe, a former presidential candidate, calling on General Ibrahim Babangida to remain in office.

Although the government denied links with the ABN, many remained convinced of the connection, which was later proven. Doubts about the election increased dramatically just two days prior to the election.

On June 10, the High Court in the capital of Abuja stunned the nation by its ruling in a case brought by the ABN, which argued for the cancellation of the election on allegations of corruption. Justice Bassey Ikpeme ordered the government not to conduct the elections until the charges had been examined and studied.

The next day, the government reassured the nation that elections would go ahead the following day, citing a military decree which ousted the authority of the High Court to decide on election-related matters. Indeed, according to Decree 13 of 1993, no court ruling could affect the date or time of the holding of an election.

Lawyers of the National Electoral Commission (NEC) said they would appeal the court’s ruling. On election day, more than 30% of registered voters went to the polls, a significant turnout in a country where many potential voters had become disillusioned by years of the government’s discouragement of popular participation and incessant manipulation of the transition. With minor exceptions, election monitors reported that the voting went fairly and smoothly.

The Nigerian Election Monitoring Group (NEMG) issued a release commending Nigerians for the “visible, high degree of political maturity and patience in the conduct of the presidential election.”

The victor was required to gain one-third of the vote in at least twenty of the thirty states. On June 14, on the billboard outside its headquarters in Abuja, NEC published results from fifteen states, showing Abiola well ahead in all regions of the country, including in Tofa’s home state of Kano. Regionalism appeared to have been, at least temporarily, an irrelevant factor in Nigerian politics.

The Annulment of the June 12, 1993, Presidential Election

After the initial posting on June 14, no additional election results ever appeared on the NEC board. On June 16, Radio Nigeria announced that NEC was suspending the announcement of election results because of “developments and actions pending in courts.” It cited a restraining order granted the day before by Justice M.D. Saleh, the chief judge of Abuja, which prohibited NEC from publishing the results.

The order had been issued in response to a motion filed by Abimbola Davies of the ABN, who charged that the elections had been plagued by corruption. Judge Saleh ruled that he would consider ordering the elections annulled, pending further investigation of the charges by ABN.

Nigerians and foreigners were stunned by the announcement, particularly, since NEC had ignored the High Court’s order less than a week earlier. A flurry of additional suits brought before the High Courts in Benin City, Lagos, Ibadan, Jos, and Awka, Anambra State, contradicted the Abuja court’s decision and resulted in orders for NEC to release the election results.

On June 18, 1993, in defiance of Decree 13’s threat of a five-year jail sentence and fine for publishing unauthenticated voting figures, the Campaign for Democracy (CD) made good its threat of the previous day and published the results, showing that Abiola had won a majority of the vote in 19 of the 30 states, with a total of 58.4% of the vote to Tofa’s 41.6%.

Calls for recognition of the results came from individuals and organisations including unions, politicians, and prominent Nigerians, such as the writer and Nobel Prize winner, Wole Soyinka who said it would be deliberately chaotic to further delay in making the verdict of the Nigerian people official.

As expected, Abiola claimed victory.

On June 21, NEC filed an appeal against the Abuja court’s order, and a hearing was scheduled for June 23. On the same day, Justice Saleh ruled that the elections were illegal because of NEC’s decision to ignore the June 10 court order not to conduct the elections until allegations of bribery were investigated.

As noted earlier, the government, citing Decree 13, had previously reassured the nation that the court lacked jurisdiction in the matter.

On June 23, the government made the announcement that the nation had feared – the election was annulled. In addition, NEC was dissolved, and Decrees 13 of 1993 and 52 of 1992 were abrogated.

The same day, the government said it would not hesitate to declare an emergency in any state where disturbances occurred. It stated that such a drastic step was necessary in order to remove the confusion created by the conflicting rulings from the various courts.

According to Babangida’s statement, the election was annulled “to save our judiciary from being ridiculed and politicised locally and internationally.”

Interestingly, the military Head of State could not have chosen a more incredible excuse. Beyond the obvious contradiction posed by the recent swearing-in of an Election Tribunal to handle election-related controversies, Decree 13 granted NEC wide-ranging powers to oversee elections.

Decree 52 outlined the transition timetable, including the swearing-in of an elected president on August 27, 1993.

Effects of the Annulment of the June 12, 1993, Presidential Election

An immediate outcry arose from all sectors of the society. Demonstrations were held in cities including Ibadan, Lagos, Ile-Ife, Modakeke, and Oshogbo. At least one protester was killed in Ibadan and others were seriously injured.

Individuals and organisations announced protests. The Lagos State branch of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), which accounts for 60% of the nation’s lawyers, called a boycott of the courts to begin on June 30, 1993.

International organisations, labour unions, religious organisations, and politicians all made statements calling for the recognition of the election. Members of the military also protested. Many middle-ranking members of the army were not happy with the military’s continued involvement in politics.

The CD called for one week of nationwide protests to begin on July 5. At a June 30 news conference announcing the protests, the CD chairman Dr Beko Ransome-Kuti urged workers to stay at home, traders and market women to close stalls and cars to stay off the roads. Students and youths were urged to organise themselves into civil defence groups and to form and man barricades and make bonfires.

On the first day of the protests, thousands of youths closed major roads in Lagos and the CD led thousands of marchers to Abiola’s home compound. Protests were also held in other cities, including Ibadan, Ilorin, Akure, and Kano.

Unfortunately, the Lagos protests turned violent when they were overtaken by local thugs known as area boys, who looted shops and rampaged through the streets. Violent gangs were reported to have engaged in ethnic attacks aimed at Hausa-Fulanis in Lagos. Police fired tear gas from helicopters and on the ground but were unable to contain mobs.

Police and military forces were deployed on July 6 to contain the violence, and, in the process, turned their weapons on peaceful protestors and innocent passers-by. The protests ended on July 7, when army tanks were sent into Lagos streets. CD estimated that more than 100 demonstrators were killed by security forces throughout the country while many more were arrested.

Unmoved by the protests, on July 5, 1993, Babangida ordered the parties to agree to join an unelected civilian government or face new elections. It was unstated but understood that Abiola would not be allowed to hold office despite being the presumed winner of the June 12 presidential election. On July 7, the SDP national chairman Tony Anenih indicated that he was willing to sacrifice Abiola in order to preserve the SDP’s share of National Assembly seats and governorships, and both parties agreed to the plan.

However, an outcry by Abiola and his many supporters within the SDP forced the party leadership to back away from this deal, and the party agreed to press ahead with the demand for Abiola to head the new government.

Meanwhile, General Ibrahim Babangida’s support continued to erode.

On July 8, 1993, the spiritual leader of Nigeria’s Muslims, Sultan Ibrahim Dasuki of Sokoto, a former friend of Babangida, threw his support behind Abiola, who said there was no other route away from the national catastrophe than the swearing-in of Moshood Abiola on August 27, 1993.

Former military ruler General Olusegun Obasanjo (retd.), who in May 1993 founded the Association for Democracy and Good Governance, became one of Babangida’s fiercest critics.

On July 12, 1993, after Obasanjo met with Major-General Muhammadu Buhari (who had been ousted by Babangida in 1985), and 10 former generals to discuss ways to force Babangida from power, the group issued a statement which included a demand “that the Babangida administration be terminated forthwith.”

That day, Babangida once again reversed himself and announced his demand for a new election. The reason cited for his change of heart was a recognition that an unelected government would lack legitimacy and stability.

Elections were then scheduled for August 14, 1993.

Predictably, Nigerians, who were still demanding that the results of the June 12, 1993, presidential election be respected, opposed the move. The SDP said it would boycott the elections while 14 of the 30 state governors also said they would block the new elections.

A statement by the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC) on July 15, 1993, summed up the feelings of many Nigerians who opposed “another presidential election and its attendant wastage, apathy, controversy, and lack of faith.”

Nigerians of all ethnic groups began leaving the cities for their home villages, fearing that a new election would result in violence. Over the next month, tens of thousands left Lagos, Kaduna and other cities where the threat of violence was greatest.

Shortly before the announcement of new elections, Abiola’s supporters had filed court papers asking the Lagos High Court “to restrain the military government from handing over in any manner whatsoever, the executive powers of the federation to any person or persons other than the person duly elected as the president…“

A hearing was scheduled for July 21, 1993, and judgment was ordered for July 23. In a related case, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a suit brought by 14 state governors seeking to reverse the election annulment.

Once again, the government stepped in to block the actions of the courts, presumably forgetting its recently avowed concern for the judiciary. On July 19, 1993, the government issued a number of decrees, one of which barred all courts from hearing cases related to the June election. The other decrees gave retroactive backing to the annulment of the election and called for new voting, but gave no date for transferring power.

On July 16, 1993, evidence that the military had engineered the political crisis for its own ends was confirmed by an inside source. Abimbola Davies, the ABN member who had filed the ABN’s suits in the Abuja High Court that resulted in orders first to halt the June 12, 1993, presidential election and then to prevent the announcement of its results, held a news conference at which he told reporters that the government had secretly organised the Abuja lawsuits in order to derail the transition and prolong Babangida’s stay in government.

In his statement, Davies begged Nigerians to forgive him and his cronies for the resulting bloodshed of Nigerians that their actions had caused during the June 12 election. At the conclusion of his remarks, Davies and his family fled the country.

Faced with continuing opposition to a new election, the government indicated that it would consider another arrangement.

Opposition to the Interim National Government

On July 27, Anenih announced that he was again ready to sacrifice Abiola and make a deal with the NRC and the military to form a new government. A few days later, General Ibrahim Babangida announced his agreement with the interim government plan. He said that the interim administration would specifically oversee local council elections scheduled for December 1993 and, at some unnamed future date, a new presidential election. Details of the plan were to be worked out by a committee headed by Babangida’s deputy, Augustus Aikhomu.

In his statements, Babangida continued to portray his erratic moves as reasonable steps in the transition process. Citing the same reasons the government had used earlier in disapproving of the idea of an unelected civilian government, Abiola quickly responded that the new plan was unworkable because of its inherent lack of legitimacy.

Popular reaction to the plan was again quick and vocal. A group of 30 senators signed a joint motion asking the government to declare the winner of the June 12 election. All but six of 30 SDP state chairmen indicated they supported Abiola and rejected the interim government proposal.

Nigerians continued to leave the cities and the government continued to insist that there was no danger.

On August 2, 1993, the CD said it would press on with civil disobedience campaign. It called “for renewed nationwide protests on 12th to 14th of August to oppose Babangida’s latest manipulation to prolong military rule.” It said the Abiola government, which had won the June 12 election, “be defended by the Nigerian people and take office on August 27.”

This time, the CD stressed the need for non-violence and urged protestors to stay close to home to avoid bloodshed. The Committee on the Interim National Government submitted its report on August 5, 1993. The Interim National Government was to then organise a new presidential election and hand over authority to an elected civilian president by March 31, 1994.

On August 4, 1993, Abiola left Nigeria unannounced in his private plane and flew to London and Washington to drum up international support for his cause. After his departure, the government made a number of unsubstantiated allegations against him, including that he was involved in a plot to bomb various strategic locations, a charge that Abiola termed “ridiculous.”

In mid-August, Abiola reported that he planned to return to Nigeria before the end of the month. Various industrial unions, including the powerful oil workers union and textile and banking unions, announced plans to embark on strikes if the military did not step down on August 27.

Obasanjo’s group, Association for Democracy and Good Governance in Nigeria, said on August 9, 1993, that the national interim government schemes are no solution to the current political impasse facing the nation. The group further urged all Nigerians to embark upon peaceful and non-violent means of expressing their disapproval should Babangida fail to leave office on August 27.

As the stalemate continued, opposition to the military started weakening in some quarters, allegedly due to bribes paid to former critics, including politicians, unions and other organisations. Human rights activists reported that individuals in their organisations were offered bribes at various times.

In mid-August, a majority of the Senate voted its approval for the interim government plan. On August 10, 1993, confronted with the upcoming strike by the CD, the government threatened to impose a state of emergency. Government employees were threatened with dismissal. Soldiers were posted on highway overpasses and bridges which had been seized by rock-throwers during previous riots.

Merchants began shutting down shops. On August 12, the strike shut down businesses in Lagos, Ibadan, the former capital of the Western Region, and other southwestern cities as Nigerian workers stayed home. The following two days were also largely quiet in the southwest, but in the north, business reportedly took place as usual.

However, the government’s response to the peaceful strike was brutal.

Attacks on Nigerian Pro-Democracy Activists

Because of the deplorable conditions of Nigeria’s prisons and detention facilities as well as the brutal tactics of security agents, there were serious concerns for the safety of all political detainees. In addition to the detentions, security agents raided the headquarters of human rights organisations on several occasions, destroyed equipment, and removed materials including membership lists.

Three leaders of the pro-democracy movement, Dr Beko Ransome-Kuti, CD chairman and president of the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights, Chief Gani Fawehinmi, a well-known human rights lawyer, and Femi Falana, President of the National Association of Democratic Lawyers, were arrested and detained at Kuje Prison in Abuja on July 10, 1993.

On July 15, the three detainees were charged before a Magistrate Court with sedition and conspiracy to incite violence. The court refused them bail and ordered that they be detained until September 30.

The next day, they were informed that, in addition to the criminal charges, they were also subject to detention under Decree 2, Nigeria’s infamous administrative detention decree, according to which any person who posed a security risk may be detained for indefinitely renewable six-week periods.

Despite serious medical concerns about both Dr Ransome-Kuti and Chief Fawehinmi, the three detainees were denied access to their lawyers, families, and doctors.

Attacks on the Nigerian Press

Since the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election, the Nigerian media suffered the worst assault in its history. Five media houses were shut down in July; four were proscribed in August. Many journalists were arrested and detained.

Babangida promulgated a new decree which stipulated a 10-year jail term for publishing “false information. A signal of further erosion of press freedom.

Attacks on the press began to intensify in the pre-election period. At the time of the elections, The Reporter, a daily based in Kaduna, had been proscribed. The News, a weekly based in Lagos, had been shut down and its editorial staff declared wanted. In July, The News changed its name to Tempo and continued to publish underground.

Tell, another Lagos weekly which started publishing in February 1993, was repeatedly harassed by security agents and had numerous issues confiscated. It went underground as well.

In the aftermath of the election’s annulment, the outspoken press became more vocal, and the government stepped up its attacks.

On June 29, 1993, the wife and three-month-old child of Dapo Olorunyomi, The News deputy editor-in-chief, were detained for 24 hours. They were thought to have been arrested in Olorunyomi’s stead, following a common practice of the Nigerian police, and were reportedly released when the child became ill.

The News was then proscribed. The July 5 edition of Tell was confiscated.

On July 21, 1993, the Minister of Information and Culture, Uche Chukwumerije claimed that a segment of the press was inciting violence and warned the media to stop publishing “negative” articles. Charging that they had accepted bribes to publish information intended to incite the public against the government, the government raided and sealed off five media houses over the next two days.

They were, Concord Press, owned by Abiola; Punch, a Lagos-based daily; The Sketch group, publisher of the Daily Sketch and Sunday Sketch, based in Ibadan, owned by four state governments; Newsday, a daily based in Abuja; and The Observer, a daily owned by the Edo State government and based in Benin City.

The Ogun State Broadcasting Corporation was also shut, then re-opened the next day after the governor agreed to “supervise and closely monitor” the broadcasts. A number of journalists were arrested, including two from Newsday, and the publication was told not to publish until further notice.

On August 16, 1993, the Babangida government issued two decrees. Decree 48 proscribed the Concord group publications, Punch, The Sketch publications, and The Observer. Decree 43 contains many restrictions on the press, including punishment by a 10-year prison term or $11,000 fine, or both, for publishing “false information”; a requirement that all newspapers register annually with the government, which also requires a steep registration fee; the creation of a registration board, whose chairman will be appointed by the government; the establishment of an office for each paper in Abuja within one year; and an order to submit all newspapers to the Information Secretary.

The financial burden imposed by the decree’s various requirements undoubtedly led to the closure of most of Nigeria’s independent presses.

Lessons of the Annulled June 12, 1993, Presidential Election

One of the reasons Babangida gave as to why he annulled the June 12, 1993, presidential election, was to save the democratic government at the time. The gap-toothed general said he was compelled to nullify the election because of security threats to the enthronement of a democratic government at the time.

According to Babangida, his regime had decided that it would be the last administration that would ascend the seat of power through a coup d’état, adding that it would make no sense to install a democratic government that would be truncated within another six months.

He, however, admitted that the June 12, 1993, presidential election was free and fair and also the best of all elections ever conducted in Nigeria’s history.

Nevertheless, Babangida was pressured by the Defence Council to stick to the handover date, and he, therefore, resigned on August 26, 1993. The country was then ruled by an Interim National Government headed by Chief Ernest Shonekan, a British-trained lawyer and businessman, with Sani Abacha, a confidant of Babangida, serving as Minister of Defence.

On November 10, 1993, a Lagos High Court ruled that the decree establishing the Interim National Government was not properly signed – it was signed by Babangida after his removal from the presidency, thus making the government illegal.

On November 17, 1993, Abacha toppled the interim government in a palace coup, dissolved the legislature, as well as the state and local governments, and replaced the elected civilian state governors with military and police officers.

In June 1994, Abiola declared himself president and commander-in-chief and was arrested and charged with treason.

The Abacha government did not stop there.

On March 10, 1995, it announced an alleged coup attempt where Olusegun Obasanjo, Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, and Beko Ransome-Kuti were among those secretly tried and either condemned to death or received long prison sentences.

Seven months later, in October 1995, Abacha set a timeframe of three years to hand over power to an elected civilian government but he died on Monday, June 8, 1998, under mysterious circumstances.

You can check out the video below to know the full story on how Abacha died and what really caused his death.

We always have more stories to tell, so make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button for interesting historical videos. Don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and to as well share this article with your friends.

You can also get Ayomide Akinbode’s latest historical novels on Amazon, Rovingheights, and Okadabooks.

Sources

Campbell, I. (1994). “Nigeria’s Failed Transition: The 1993 Presidential Election”. Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 12 (2): 179–199. doi:10.1080/02589009408729556

dawodu.com (n.d). “Text of IBB Broadcast to the Nation (June 26, 1993)”. Retrieved from https://dawodu.com/ibb6.htm

Elezuo, E. (2018). “Read Abimbola Davies’ Confession of How June 12 1993 Election was Scuttled”. Retrieved from http://thebossnewspapers.com/2018/06/08/read-abimbola-davies-confession-of-how-june-12-1993-election-was-scuttled/

Lewis, P. (1994). “Endgame in Nigeria? The Politics of a Failed Democratic Transition”. African Affairs. 93 (372): 323–340. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098722. JSTOR 723365.

News from Africa Watch (1993). “Nigeria, Democracy Derailed: Hundreds Arrested and Press Muzzled in Aftermath of Election Annulment”. Human Rights Watch. 5 (11): 1–21.

Ogbeidi, Michael M. (2010). “A Culture of Failed Elections: Revisiting Democratic Elections in Nigeria, 1959-2003”. Historia Actual Online. 21: 43–56.

Ogunmade,O. (2009). “IBB: The Real Reason I Annulled June 12”. Retrieved from https://maxsiollun.wordpress.com/2009/02/07/babangida-the-real-reason-i-annulled-june-12/

Omoruyi, O. (2012). “The basis for the annulment of June 12”. Retrieved from https://www.vanguardngr.com/2012/06/the-basis-for-the-annulment-of-june-12-by-omo-omoruyi/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

View Comments