No products in the cart.

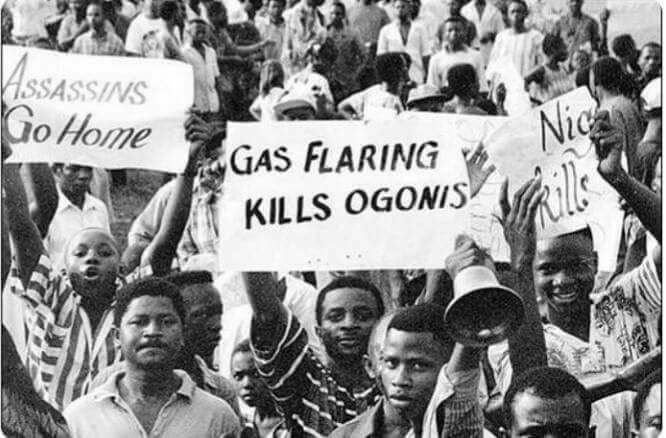

Kenule Beeson ”Ken” Saro-Wiwa (October 10, 1941 — November 10, 1995) was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority in Nigeria whose homeland, Ogoniland, in the Niger Delta has been targeted for crude oil extraction since the 1950s and which has suffered extreme environmental damage from decades of indiscriminate petroleum waste dumping.

Initially as spokesperson, and then as president, of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), Saro-Wiwa led a nonviolent campaign against environmental degradation of the land and waters of Ogoniland by the operations of the multinational petroleum industry, especially the Royal Dutch Shell company. He was also an outspoken critic of the Nigerian government, which he viewed as reluctant to enforce environmental regulations on the foreign petroleum companies operating in the area.

Ken Saro-Wiwa: Early Life and Education

Born Kenule Tsaro-Wiwa, the son of Jim Wiwa (1904-2005), a forest ranger, and his third wife, Widu. He changed his name to Saro-Wiwa after the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970). His father’s hometown is the village of Bori, Ogoniland whose residents speak the Khana dialect of the Ogoni language.

Contents

Ken Saro-Wiwa spent his childhood in an Anglican home and eventually proved himself to be an excellent student; he received primary education at a Native Authority school in Bori, then attended secondary school at Government College Umuahia.

A distinguished student, Saro-Wiwa was captain of the table tennis team and amassed school prizes in History and English. At Umuahia, he was the only student from Ogoni land but fellow students were mandated to speak English which made Saro-Wiwa feel Nigerian; he embraced the language as a useful way to communicate to a larger audience at home and abroad.

On completion of his secondary education, he obtained a scholarship to study English at the University of Ibadan. At Ibadan, plunging into academic and cultural interests, he won departmental prizes in 1963 and 1965 and worked for a drama troupe.

Career and Civil War

Ken Saro-Wiwa briefly became a teaching assistant at the University of Lagos and later at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He was an African literature lecturer in Nsukka when the Civil war broke out, he supported the Federal Government and had to leave the region for his hometown of Bori.

On his journey to Port-Harcourt, he witnessed the multitudes of refugees returning to the East, a scene he described as a “sorry sight to see“. Three days after his arrival, nearby Bonny was liberated by federal troops. He and his family then stayed in Bonny, he travelled back to Lagos and took a position at UNILAG which did not last long as he was called back to Bonny.

Ken Saro-Wiwa was called back to become the Civilian Administrator for the port city of Bonny in the Niger Delta and during the Nigerian Civil War positioned himself as an Ogoni leader dedicated to the Federal cause. He followed his job as an administrator with an appointment as a commissioner in the old Rivers State.

His best-known novel, Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English tells the story of a naive village boy recruited to the army during the Nigerian Civil War and intimates the political corruption and patronage in Nigeria’s military regime of the time.

Personal Life and Family

Saro-Wiwa and his wife Maria had five children, who grew up with their mother in the United Kingdom while their father remained in Nigeria. They include Ken Wiwa and Noo Saro-Wiwa, both journalists and writers, and Noo’s twin Zina Saro-Wiwa, a journalist and filmmaker. In addition, Saro-Wiwa had two daughters (Singto and Adele) with another woman. He also had another son, Kwame Saro-Wiwa, who was only 1 year old when his father was executed.

Activism

In 1990, Saro-Wiwa began devoting most of his time to human rights and environmental causes, particularly in Ogoniland. He was one of the earliest members of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), which advocated for the rights of the Ogoni people. The Ogoni Bill of Rights, written by MOSOP, set out the movement’s demands, including increased autonomy for the Ogoni people, a fair share of the proceeds of oil extraction, and remediation of environmental damage to Ogoni lands. In particular, MOSOP struggled against the degradation of Ogoni lands by Royal Dutch Shell.

In 1992, Saro-Wiwa was imprisoned for several months, without trial, by the Nigerian military government. In January 1993, MOSOP organised peaceful marches of around 300,000 Ogoni people – more than half of the Ogoni population – through four Ogoni urban centres, drawing international attention to their people’s plight. The same year the Nigerian government occupied the region militarily.

Trial and Execution

On May 21, 1994, four Ogoni chiefs (all on the conservative side of a schism within MOSOP over strategy) were brutally murdered. Saro-Wiwa had been denied entry to Ogoniland on the day of the murders, but he was arrested and accused of incitement to them. He denied the charges but was imprisoned for over a year before being found guilty and sentenced to death by a specially convened tribunal. The same happened to eight other MOSOP leaders who, along with Ken Saro-Wiwa, became known as the Ogoni Nine.

Some of the defendants’ lawyers resigned in protest against the alleged rigging of the trial by the Abacha regime. The resignations left the defendants to their own means against the tribunal, which continued to bring witnesses to testify against Saro-Wiwa and his peers.

On November 10, 1995, Ken Saro-Wiwa and the rest of the Ogoni Nine were killed by hanging by military personnel. They were buried in the Port-Harcourt Cemetery. Saro-Wiwa was 54.

It took five attempts to hang Ken Saro-Wiwa before he spoke his last words and his body went limp. “Lord take my soul, but the struggle continues,” were his final words before he died blindfolded and dangling from a rope.

Kenule Beeson Saro-Wiwa Polytechnic, formerly Rivers State Polytechnic, is named after him. Also, a street in Amsterdam, Netherlands, has been named after Saro-Wiwa; the Ken Saro-Wiwastraat.

We always have more stories to tell. So, make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button to receive notifications for interesting historical videos. Also, don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and to as well share this article with your friends.

Feel free to join our YouTube membership to enjoy awesome perks. More details here…

Sources

Aigbogun, F. (1995, November 13). It took five tries to hang Saro-Wiwa. Associated Press. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/it-took-five-tries-to-hang-sarowiwa-1581703.html

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, November 6). Ken Saro-Wiwa. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ken-Saro-Wiwa

Kriesch, A. (2015, November 09). Ken Saro-Wiwa executed 20 years ago. DW. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/why-nigerian-activist-ken-saro-wiwa-was-executed/a-18837442

Doron, R., Falola, T. and Seay, L. (2016, July 29). The complex life and death of Ken Saro-Wiwa. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/07/29/the-complex-life-death-of-ken-saro-wiwa/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

View Comments