No products in the cart.

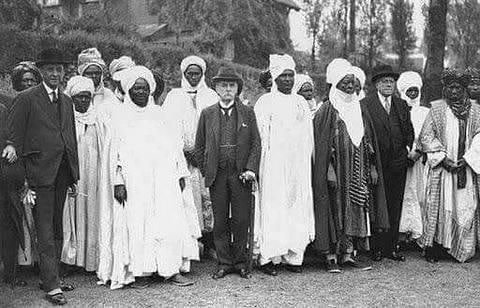

On January 1, 1914, Lord Frederick Lugard succeeded in the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern Provinces of Nigeria to make up for what is now known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Frederick Lugard, who had assumed the office of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria high commissioner in 1900, has often been considered the British colonial administrator model.

So, why did Lugard join two different countries as one in the same year the First World War began?

Frederick Lugard

Trained as an army officer, Frederick Lugard had served in India, Egypt, and East Africa, expelling Arab slave traders from Nyasaland, and establishing the British presence in Uganda.

Contents

In 1894, Lugard joined the Royal Niger Company and was sent to Borgu to counter French inroads, and in 1897 he was made responsible for raising the Royal West African Frontier Force from local duties to serve under British officers.

Throughout his term as the High Commissioner of Northern Nigeria, Lugard was busy turning the economic sphere of influence inherited from the Royal Niger Company into a viable territorial body under strong British political control.

His aim was to conquer the region as a whole and obtain recognition by its indigenous rulers, particularly the Sokoto Caliphate Fulani emirs, for the British protectorate.

Lugard’s campaign actively suppressed local resistance and used armed force after failure of diplomatic initiatives.

In 1903, Kanem-Bornu surrendered to Lugard’s Armed Forces without a fight. However, Lugard mounted attacks on Kano and Sokoto.

From the point of view of Lugard, clear-cut military victories were important, otherwise, their surrenders weakened the resistance.

Indirect Rule in Northern Nigeria

Lugard’s popularity in Northern Nigeria was due to his policy of indirect rule, which requested that the rulers who had been defeated administer the protectorate.

If the Emirs embraced British authority, abolished the slave trade and cooperated with British officials to modernise their government, the colonial power was willing to confirm them in office.

The emirs kept their titles of caliphate but were accountable to British district officials, who had final authority. Emirs and other officials could be deposed by the British High Commissioner if necessary. Lugard sharply reduced the number of titled fief holders in the emirates, which undermined the influence of the rulers.

Caliphate officials were converted under indirect rule into salaried district heads and became, in essence, agents of the British authorities, responsible for peacekeeping and tax collection. The old chain of command was merely capped with a new overlord, the high commissioner of Britain.

The protectorate required only a limited number of colonial officers who were dispersed as overseers throughout the territory.

They exercised discretion in advising the emirs and local officials, depending on local circumstances but all instructions from the high commissions were transmitted through the emir.

Though the high commissioner in the protectorate possessed unlimited executive and legislative powers, most of the government’s activities were undertaken by the emirs and their local administrations, subject to British approval.

A dual system of law worked— the sharia court (Islamic law) tended to deal with matters concerning Muslims’ personal status, including land disputes, divorce, debt, and slave emancipation.

As a result of indirect rule, the domination of Hausa-Fulani was confirmed – and in some cases forced on diverse ethnic groups, some of them non-Muslim, in the so-called middle belt of Nigeria.

The accomplishments of Lugard and his successors in economic development were limited by the revenues available to the colonial government. One of Lugard’s initial acts was to separate the general treasury of each emirate from the emir’s privy purse.

From taxes collected by local officials, first one-quarter and later one-half was taken to support services of the colonial regime, which were meager because of the protectorate’s lack of public resources.

Indirect Rule in Southern Nigeria

In the south, missionaries made up for the lack of government expenditure on services; in the north, Lugard and his successors limited the activities of missionaries in order to maintain Muslim domination.

Consequently, educational and medical services in the north lagged behind those in the south. Progress was made in economic development, however, as railroad lines were constructed to transport tin from Jos-Plateau and northern-grown peanuts and cotton to ports on the coast which were subsequently sent to England.

Efforts to apply indirect rule to the south, which formally became a protectorate in 1906, in emulation of Lugard’s successful policy in the north set off a search for legitimate indigenous authorities through whom the policy could be implemented.

The task proved relatively easy in Yorubaland, where the governments and boundaries of traditional kingdoms were retained or, in some instances, revived.

Among the Igbos of the southeast, where Aro hegemony had been crushed, the search for acceptable local administrators was met with frustration.

As a result, the tasks of government initially were left in the hands of colonial officials, who antagonized many Igbo. The Igbo therefore stressed traditional egalitarian principles as a justification for their early opposition to colonial rule; in Yorubaland and in the north, the devolution of administrative duties to the indigenous ruling elites contained much of the early opposition. Resistance to colonial rule was mitigated to the extent that local authorities and courts were able to manage affairs.

The British prohibited the enslavement of free persons and suppressed slave trading. All children in the north who were born to persons in bondage on or after April 1, 1900, were declared free.

The relations between existing slaves and their owners, however, were allowed to continue indefinitely, on the assumption that wholesale liberation would cause more harm than good by disrupting the agricultural economy. As a consequence, at least several hundred thousand slaves deserted their masters in the early years of colonial rule.

In 1906 a radical Muslim uprising that received the support of many fugitive slaves was brutally crushed. In the south, slaves legally could be forced to return to their owners until 1914. In the north, vagrancy laws and the enforcement of proprietary rights to land were used to tax to check the flight of slaves.

Slaves in the northern emirates could secure their freedom upon application to an Islamic court, but comparatively few used this option.

Throughout the colonial period in the Muslim north, many slaves and their descendants continued to work for their masters or former masters and often received periodic payments leading to emancipation.

The Amalgamation of Nigeria

In 1912, Frederick Lugard was appointed Governor-General of both Southern and Northern Nigeria with the mandate to unite the two Protectorates. His main mission was to complete the amalgamation into one colony.

Northern Nigeria at 716,880 km², occupy 77.6% of Nigeria’s land mass which is nearly four times the size of Southern Nigeria at 206,888 km².

Although controversial in Lagos, where it was opposed by a large section of the political class and the media, the amalgamation did not arouse passion in the rest of the country.

From 1914 to 1919, Lugard was made Governor-General of the now combined British Colony of Nigeria.

The amalgamation was done for economic reasons rather than political. Northern Nigeria Protectorate had a budget deficit; and the colonial administration sought to use the budget surpluses in Southern Nigeria to offset this deficit.

The disparities between the Protectorates were to be corrected by creating a central administration in Lagos, with custom revenues from the South paying for the projects in the North.

Lugard ran the country with half of each year spent in England, distant from realities in Africa where subordinates had to delay decisions on many matters until he returned, and based his rule on a military system.

We always have more stories to tell, so make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button for interesting historical videos. You can also follow us on all our social media handles and don’t hesitate to as well share this article with your friends.

You can also get A Carnage Before Dawn, a historical account of Nigeria’s first coup d’état. Paperback here. And on Amazon Kindle and Amazon Paperback.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply

View Comments