No products in the cart.

On January 4 and 5, 1967, delegates and representatives from both the Federal Government of Nigeria and the Eastern Region, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Emeka Ojukwu, met in Aburi, Ghana to agree on what is now known as the Aburi Accord. The meeting at Aburi was supposed to be the last opportunity to avoid any conflict or civil war. Unfortunately, it was not to be.

So, what really happened in Aburi, Ghana, in 1967 that eventually led to the Nigerian Civil War?

Contents

The Genesis of the Aburi Accord

After the first military coup that installed Major-General Johnson Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi as Nigeria’s first military Head of State on January 16, 1966, the Northern soldiers had started planning, by May 1966, the revenge of their leaders who had been murdered in January. The Northerners were the major casualties of that coup that was carried out by soldiers mainly from the East.

To them, it was an Eastern-favoured coup as Aguiyi-Ironsi’s regime was believed to be extremely partisan. This highlighted the feeling of insecurity of other groups. It created more problems than it solved old ones which led to severe criticism of the Supreme Commander.

The General himself may not have been necessarily nepotistic. Rather, he failed to see the sectional and clannish implications of events, policies, and appointments that were made during his tenure of office.

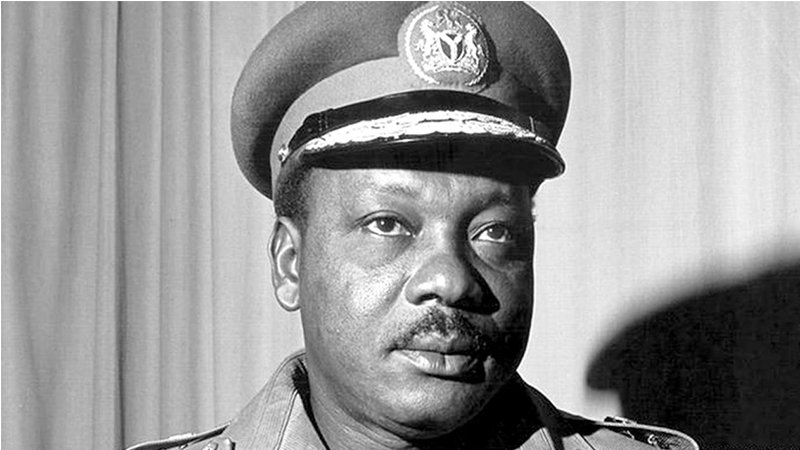

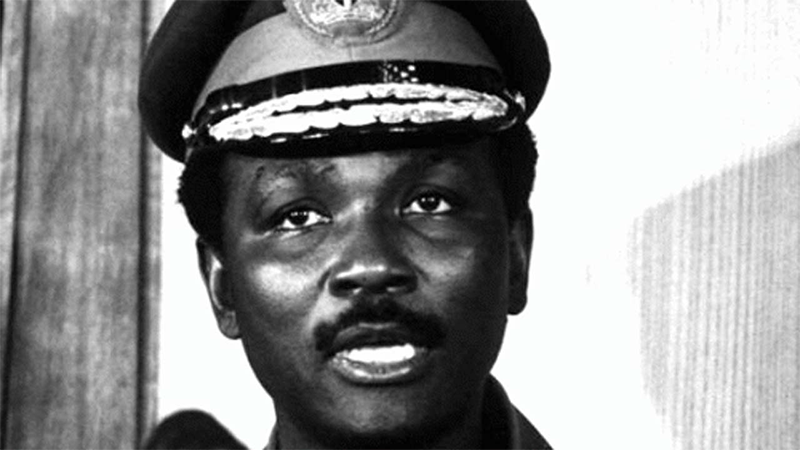

One hundred and ninety -four days after taking office, Aguiyi-Ironsi was murdered in a Northern counter-coup on July 29, 1966. The nation had no leader for three days until Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon succeeded the late Head-of-State on August 1, 1966.

Significance of the July 29, 1966, Coup

The immediate significance of the July coup was that it forced a return to an ethnic balance within the Army as neither the major ethnic groups, Hausa or Yoruba, was placed in power but a minor ethnic group from the Northern Region in present-day Plateau State.

In the confusion that followed the second coup d’état, the slender confidence that remained between the Igbo and the Northerners was shattered. Disturbances broke out in the East but even more so in the North after August 1, 1966.

The mass killings of the Igbo in the North were a deplorable act that was condemned by Nigerians, including the Military Governors.

With the Northern counter-coup of July 29, 1966, the political development of Nigeria’s federal structure took a different turn. It was accentuated even more by the fact that the Eastern Region Government in Enugu immediately threatened secession if certain grievances and demands were not met.

The immediate concern of the Federal Government, therefore, was for it to find ways to appease the East so long as such concessions were within the framework of one Nigeria.

On the Road to Aburi

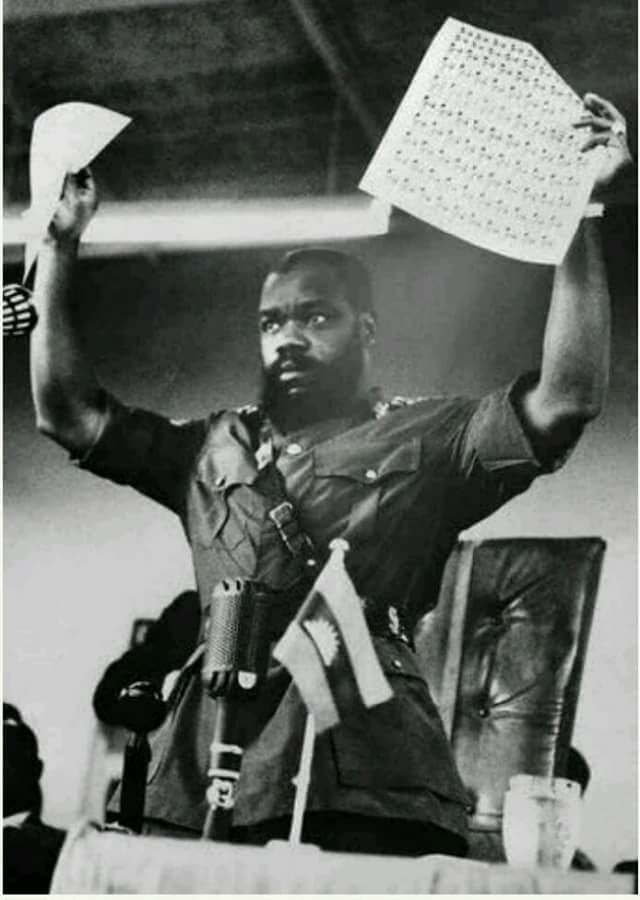

Claiming he was not safe outside the East, the Eastern Military Governor, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu refused to leave the Region for any meeting anywhere in Nigeria. In a rejoinder, the Federal Government too argued that the Nigerian leader, Yakubu Gowon should also not go to the East for a meeting. His life, they also claimed, was not safe there either. Tension mounted and Lieutenant-General Joseph Arthur Ankrah of Ghana offered a neutral meeting place. The venue was Aburi, Ghana.

The Aburi meeting started on January 4, 1967, and lasted two days.

Those who attended the meeting included Head of State Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon, and the Military Governors of the four regions: Hassan Usman Katsina of the Northern Region, Robert Adeyinka Adebayo, David Akpode Ejoor, and Chukwuemeka Ojukwu of the West, Mid-West, and Eastern Region respectively.

Others included the Military Administrator of Lagos, Mobolaji Johnson, the Head of the Nigerian Navy, Commodore Joseph Edet Akinwale Wey, and the Inspector-General of Police, Alhaji Kam Selem, among others.

The Significance of Aburi

Aburi was significant for several reasons. First, that the leaders met at all was an achievement in itself. But even more tangible was the fact that the leaders agreed that force would not be used to settle the “brothers’ palaver”. There was also the question of the disposition of Nigerian troops and the reorganisation of the Army after the second coup on July 29, 1966, and the subsequent killings that followed in May and September.

Further, Ojukwu said that his Region was perturbed that contrary to Gowon’s promise on August 9, 1966, that all soldiers would return to their Region of origin, Northern troops still “occupied” the Western Region.

Gowon replied that his promise of August 9, applied to the repatriation of soldiers of Northern origin stationed in the East back to the North and those of Eastern origin stationed in the North back to the East. He had fulfilled his promise, he said. He then emphasised that soldiers of Northern origin would remain in the West since there were only a few Yoruba in the Nigerian Army.

The Brothers’ Palaver

Ojukwu was not satisfied and further insisted on a reorganisation of the Army on a Regional basis. Gowon was also firmly opposed to splitting up the Army.

Ojukwu claimed that Nigeria did not have a central government since the country as a result of the second coup and its aftermath resolved itself into three separate sovereign areas; the Lagos-West-North Area, the Mid-West Area, and the East Area. But Gowon insisted that Nigeria was still one nation, an entity composed of four regions and a central government in Lagos.

Ojukwu then proposed that the situation in the nation necessitated “a drawing apart” of the Regions because “the separation of forces, the separation of the population is, in all sincerity, necessary in other to avoid further friction and further killings.” The other leaders who all wanted “One Nigeria” agreed to Ojukwu’s proposal, but apparently without understanding the implications. This was the bombshell of Aburi.

Why the Aburi Accord Failed

By agreeing to Ojukwu’s argument at Aburi that the Regions should first “pull apart” in order to stay together, the other leaders in effect sanctioned Biafra’s secession, hence, the end of Nigeria as a single nation.

They attended and left the Aburi meeting with the firm belief that Nigeria should and would continue as one nation. But they had gone to that meeting, as it seems, without adequate preparations in terms of a crew of legal and political advisers which such a meeting demanded. They had gone to Aburi in a spirit of comradeship.

Ojukwu, on the other hand, meant business. He arrived in Aburi with a strong team of legal, political, and economic advisers, secretaries, and realms of paper.

Not only did the other leaders at Aburi agree with Ojukwu that the Regions and peoples of the nation first “draw apart”, but they also agreed to the latter’s suggestion that there should be no Supreme Commander of the Army, hence, no Head of Government or Head of State.

What Ojukwu wanted was that whoever was at the top should be a titular head, who would only act when all of them had met and taken a unanimous decision.

Since the unanimous decision of all the Regions was required before he could act in all matters which affected any of the Regions or the nations as a whole, the Commander-in-Chief and Head of a Government was so only in name; he would still be “a titular head”.

The point of the agreement at Aburi was that each region would be responsible for its own affairs and that the Federal Military Government would be responsible for matters that affected the entire country: a simple enough concept.

Afterwards, the officers toasted their reconciliation and agreement with champagne. The federal delegation’s jubilation was such that on his plane flight home from Aburi, Ojukwu asked one of his secretaries whether the federal delegation had fully understood the implications of what had been agreed.

However, no one at Aburi, other than Ojukwu, understood the constitutional implications of what had been agreed. Ojukwu was delighted with this – hence, why he was in such a hurry to implement the decisions taken, and why the Gowon had to break his promise.

The Role of the Permanent Secretaries

Federal Permanent Secretaries, who headed the various Ministries of the Government as of then, as well as political and legal experts in the country, were appalled at the content of the Aburi Agreement when their leaders returned home from Aburi, Ghana. The Permanent Secretaries met on January 20, 1967, to evaluate the Agreement and they rightly argued that the title of “Commander-in-Chief” was a subtle way of either abolishing the post of the Supreme Commander or declaring it vacant, now that its previous occupant, Major-General Aguiyi-Ironsi, was dead.

They further reported that the proposal that all appointments to top posts in the Military, Civil Service, and the Diplomatic Corps be unanimously approved by the Supreme Military Council, would tend to paralyze the functions of the Federal Public Service Commission.

They also noted that the allegiance and loyalty of the regionally-appointed officers of the Federal Government would be to regions, meaning in effect that there would be no Federal Public Service.

The summary of their report was that the Aburi Agreement summed up to a confederation. The leaders themselves were shocked.

Then, from February 16 through February 18, 1967, Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon summoned a meeting of the secretaries to the military governments and other officials which was held in Benin City over a memo one of the Permanent Secretaries had written concerning the Aburi Accord.

The memo traced the long, hard road that Nigeria had travelled and stressed the need to keep a united nation.

The Permanent Secretary who wrote this memo was Prince Solomon Akenzua, who later, as Erediauwa the First, became the 39th Oba of Benin on March 23, 1979.

However, Prince Akenzua was an outstanding civil servant. In fact, he rose to become the Federal Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Health, before he retired in 1973.

Akenzua, in the memo, said that Gowon had given too much away in Aburi and that it would lead to the destruction of the country. He also said that Gowon had “legalised” total regionalism which “would make the centre very weak.”

Prince Akenzua further alluded in his memo that a weak centre would lead to a confederation and a total disintegration of Nigeria.

The shocking revelation of the meeting of the Aburi Agreement overshadowed some of the important decisions the leaders agreed to at Aburi in their search for peace and for a new basis of a stable federal union, or at least, a national unity.

Aburi on the whole was a big success, but the interpretation of what transpired at the meeting devalued the success. Ironically, implementing the decisions agreed on at Aburi was necessary. Ojukwu then set March 31, 1967, as a deadline for unilateral implementation of the Aburi Accord.

Gowon, on the other hand, broke his promise and restated that the constitutional changes the East proposed at Aburi would not work because such changes would result in the end of Nigeria as a single nation.

As Prince Akenzua had written in his memo, Gowon had given too much away in Aburi that would have led to the destruction of the country. He “legalised” total regionalism which “would make the centre very weak.” A weak centre would eventually lead to a confederation and total disintegration of Nigeria.

Decree No. 8

While the Federal Permanent Secretaries were evaluating the Aburi document to which their leaders were signatories, Ojukwu and the East had grown tougher with their demands. On their own, the other military leaders on March 17, 1967, issued a significant policy, Decree No. 8, which conferred far more powers on the Regional Governments ever than before. This was deliberately done in the hope that the new and greater degree of decentralization would placate the East so that it would not secede and a potentially consequent brutal war would be avoided.

Let us take a look at the contents of the decree:

• Legislative and executive powers in matters affecting or relating to trade, commerce, industry, transport, the Armed Forces, the Nigerian Police, Higher Education, and the territorial integrity of a Region shall be with the unanimous approval of all the four Regional Military Governors.

• The legislative and executive powers of the Regions have been fully restored and vested in their respective Military Governors, but no Region shall exercise its executive authority so as to impede or prejudice the exercise of the executive authority of the Federation or to endanger the continuance of federal government in Nigeria.

• The Supreme Military Council can take over the executive and legislative functions of a Regional Government during any period of emergency which might be declared in respect of that Region by the Supreme Military Council. The Supreme Military Council can also take appropriate measures against a Region that attempts to secede from the rest of the Federation.

• The appointment, tenure of office and terms of service of High Court judges, the functions of the Public Service Commission, the establishment of a Consolidated Revenue Fund, etc., and Edict made shall come into operation only with the concurrence of the Supreme Military Council, that is, all of these appointments by any Regional Military Governor can only take effect with the approval of the Supreme Military Council.

• Each Military Governor now controls the appointment of judges of the High Court of his Region. But the appointment of the judges of both the Supreme Court of Nigeria and the High Court of Lagos is made the sole responsibility of the Supreme Military Council.

• All appointments to posts in the super-scale group 6 and above in the Public Service of the Federation and appointments to posts of Deputy Commissioner of Police and above in the Nigeria Police Force are now to be made by the Supreme Military Council.

• Appointments to the offices of Ambassador, High Commissioner, and other principal representatives of the Republic in countries other than Nigeria are now, under the Decree, to be made by the Supreme Military Council.

This Decree No. 8 ignored the report of the Permanent Secretaries but did not fully concur with Ojukwu’s demands. It also decentralized the Government to such an extent that the Regions were virtually autonomous units in each of which each Regional Governor had executive powers.

However, Ojukwu rejected the decree because a part of the decree stated that, “no Region shall exercise its executive authority so as to impede or prejudice the exercise of the executive authority of the Federation or to endanger the continuance of federal government in Nigeria.”

Further, it provided that the Supreme Military Council can also take appropriate measures against a Region that attempts to secede from the rest of the Federation and could take over the functions of that region.

The part Ojukwu and his Easterners hated the most stated that the Federal Government could declare a state of emergency in any Region which violated any of the above provisions, on the consent of the remaining three Regions instead of the unanimous decision of all the four Regions.

As a result, Ojukwu set March 31, 1967, as the “D-Day” for the unilateral implementation of the Aburi agreement. But the East did not secede. Instead, it seized all Federal revenue that came from that part of the country.

Why Nigeria’s 12 states were created

In the meantime, the Yoruba people were dissatisfied with the presence of troops of Northern origin who occupied the Western Region and the decision to recruit Yoruba people into the Army did little to ease those feelings. So, the Yoruba through Chief Obafemi Awolowo proposed that should Ojukwu and the East secede, the West would feel free to follow suit. The Federal Government was caught pants down while Ojukwu and his followers in the East popped champagne.

While the Federal Government was still trying to steady itself from these revelations, the Northern leaders made an astonishing suggestion – the creation of more states. The nation was stunned.

Before Aburi, the question of the creation of more states, particularly in the North, had been a perennial issue that Northern politicians had always resisted. Thus, Southerners had accused the North of trying to “dominate” Nigeria forever. They also believed that the Nigerian crisis would be over if the North accepted that power could be shared. Breaking up the North into more states, which was what the East and other parts of the nation wanted, would provide the answer.

The Northern decision was a pleasant surprise to most of the nation, particularly the minority people of the North, that is, the Middle-Belt areas, and those of the Cross River-Ogoja-Rivers area, which the Ojukwu would later claim as part of Biafra. Because of this, Ojukwu did not agree to the Northern declaration for the creation of more states.

The Yoruba people, who had been one of the ardent advocates for the creation of more states, felt pleased with this unprecedented Northern move and they eventually threw their support behind the Federal Government.

Now energized, the Federal Government was ready for a showdown with Ojukwu as the authorities in the Eastern Region executed some acts which provoked the Federal Government.

These acts included the seizure of over 200,000 pounds worth of produce belonging to the Northern Region Marketing Board that was in Port-Harcourt in the East awaiting shipment. The confiscation of one-third of the entire rolling stock of the Nigerian Railway as well as 115 oil tankers. Other acts included the seizure, also at Port-Harcourt, of a Nigerian Airways DC-3 aircraft that had left the Ikeja Airport earlier on the same day on April 5, 1967.

A week later, three Igbo gunmen in civilian clothes highjacked another plane belonging to the Nigerian Airways which was flying from Benin in the Mid-West Region to Lagos. The Federal Government immediately halted all further flights to the Eastern Region. Terrorist activities in Lagos and other parts of the country heightened tension.

On Aburi We Stand: Ojukwu Declares Biafra

Before long, the sanctions against the East were beginning to bite as a result of an economic blockade of the Eastern Region in early May 1967.

A few days later, on May 26, 1967, Ojukwu addressed the East’s Consultative Assembly consisting of some 300 delegates from all provinces in the East. He declared, “There is no power in this country or in all of Black Africa that would be able to subdue us by force.” It was left to the Assembly, Ojukwu continued, to choose one of these three alternatives:

1. Accepting the terms of the North and Gowon and thereby submitting to the domination from the North.

2. Continuing the present stalemate and drift, or

3. Ensuring their survival by declaring their autonomy.

The assembly got the message. For whatever it was worth, it gave Ojukwu the powers and urged him to declare at an early practicable date for Eastern Nigeria as a free, sovereign, and independent state by the name and title of the Republic of Biafra.

Gowon announces the creation of Nigeria’s 12 states

The authorities in Lagos had anticipated the move and had prepared for it. On May 27, 1967, four months after the Aburi Agreement, Gowon declared a state of emergency for the entire nation and announced that he had assumed “full powers for the short period necessary to carry out the measures which were now urgently required”. Decree No. 8 which was promulgated deliberately to appease Ojukwu and the East was abrogated.

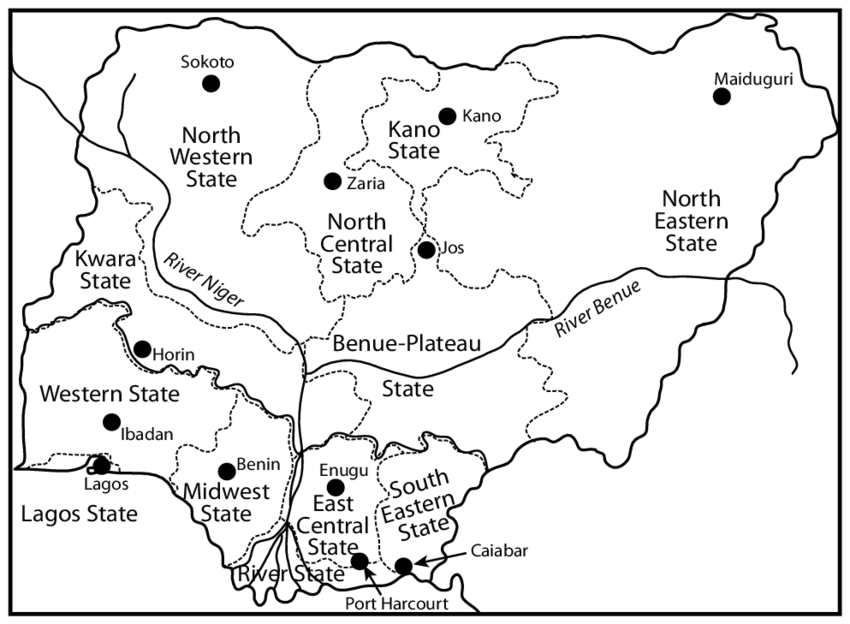

Gowon also announced that Nigeria was divided into more states, 12 in all. Nigerians were jubilant as the minorities felt secure and out of domination by the majority of people within the former regions.

The Northern Region was broken into six states (North-Western, North-Central, North-Eastern, Benue-Plateau, Kano, and Kwara), thereby cracking its monolithic posture.

The East was broken into three, with the Igbo people having their own state (East-Central) and the non-Igbo “minority” peoples in the East, two of their own states (Rivers and South-Eastern).

The Mid-West remained as it was. Some areas of the Western Region, like Yaba, Ikeja, and Ikorodu, were carved out and merged with the Federal Territory of Lagos to form Lagos State. What remained of the Western Region became Western State.

The creation of more states in the country, not a part of the agreement at Aburi, pushed the East-Central State, the Igbo heartland, into an interior pocket, cut off from the coastal oil reserves and its two seaports of Port-Harcourt and Calabar. Thus, the lack of seaports for the East-Central State was not unique.

For the secessionists, the creation of more states was a bombshell, a political reality that they refused to accept or even believe. They began to speed up the withdrawal of the Eastern Region which would include, according to them, the two new states of Rivers and South-Eastern, with capitals in Port-Harcourt and Calabar respectively.

On May 30, 1967, Ojukwu proclaimed that “the territory and Region known as Eastern Nigeria, together with her continental shelves and territorial waters, shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title, The Republic of Biafra.”

A new flag was hoisted in public buildings in the East and the Police and Army appeared in different uniforms. A national anthem that sounded like Sibelius’ Finlandia and which the former president, Nnamdi Azikiwe later claimed was plagiarised from his poem, Ode to Onitsha, was broadcast.

While nothing particularly dramatic happened for the next 30 days, the atmosphere was tense.

Though Gowon had his own share of the blame especially his carelessness after Aburi, he did everything possible to prevent the Nigerian balloon from bursting and to appease Ojukwu to the extent that many Nigerians were doubting whether the Federal Government was a sick dog that could neither bark nor bite. Nigeria’s political instability had now been pushed to its limit.

Gowon announces the beginning of the Nigerian Civil War

On July 6, 1967, the Federal Government mounted what she initially termed a “Police action” to arrest the secession. Subsequent events soon showed that it was not a mere “Police action”. It was much more serious than that, particularly with the rebel capture of the Mid-West Region through another Igbo-engineered plot in the small Benin garrison on August 9, 1967.

The assault on the Mid-West had been a miscalculation that led to the “Mid-West Boomerang” when the Federal Military Government mounted a counter-offensive with Lieutenant-Colonel Murtala Muhammed at the forefront.

The secession was now such that it could not be stopped by just a “Police action” and the result, after the Aburi Accord, was a 30-month cruel civil war in which over one million innocent civilians’ lives were lost, equipment worth billions of dollars wasted, and thousands of stalwart soldiers on both sides, dead.

In the end, the Biafrans surrendered unconditionally and pledged their allegiance to Nigeria and the Civil War officially ended on January 15, 1970, after Ojukwu had fled to Cote d’Ivoire and his deputy Philip Effiong declared an end to the Republic of Biafra.

Your support can make a world of difference in helping us continue to bring Nigeria’s rich history to life! By donating to HistoryVille, you’re directly contributing to the research, production, and storytelling that uncover the incredible stories of our past. Every donation fuels our mission to educate, inspire, and preserve our heritage for generations to come.

Additionally, if you’re a business or brand, running adverts with us is a powerful way to reach an engaged audience passionate about history and culture while supporting content that matters.

We always have more stories to tell, so make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button for interesting historical videos. You can also follow us on all our social media handles and don’t hesitate to as well share this article with your friends.

You can also get A Carnage Before Dawn, a historical account of Nigeria’s first coup d’état. E-book here. Paperback here. And on Amazon Kindle and Amazon Paperback.

Leave a Reply

View Comments